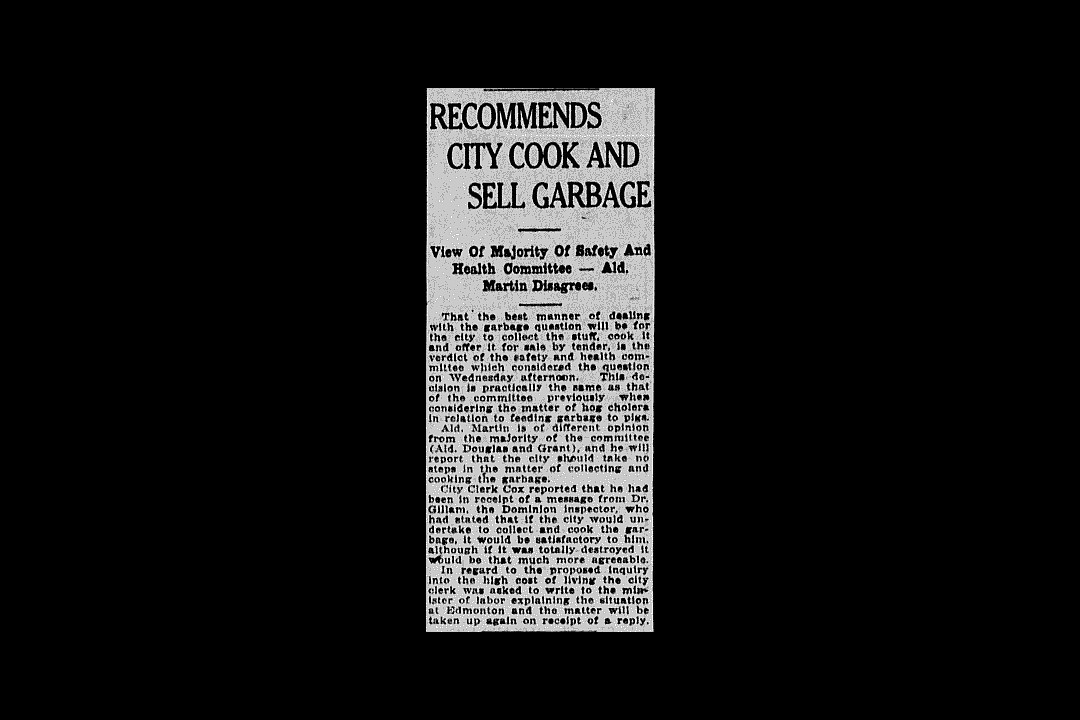

On this day in 1917, Edmonton gave a short-lived thumbs-up to a plan to cook and sell the city's trash.

What should be done with waste was a major question for many cities in the 1900s, Edmonton among them. In its earlier days, there was no organized process for getting rid of trash. Most people just dumped it out on the street. From there, it would be collected by scavengers and scrappers, who made a living from collecting and selling what others had abandoned. Household garbage could be cleaned and sold; metal, ash, and wood could be used for construction; and food slops could feed livestock.

And, when all else failed, you could always just toss your trash in the river valley. That was the official advice of the city's engineering office.

And so, the river valley became the city's trash receptacle. The escarpment where the Hotel Macdonald now stands was a particularly convenient and popular place to dispose of trash. So popular that it formed a vast collection of food waste, household goods, and refuse, which soon became known as the Grierson Dump.

But the Grierson Dump wasn't just home to waste. Soon, people began to move in, drawn by the possibility of finding treasure among the trash. A shantytown sprung up, housing mostly young men who would scour the dump for scrap to salvage and sell.

While the engineering office might have encouraged the dump, others weren't so keen. Police felt the shantytown was a hotbed for crime. Firefighters often had to battle blazes at the dump. And those living near the refuse grounds complained of flies that "swarm into houses" and a stench that remained "even in cold weather."

In 1913, an outbreak of cholera in hogs spread among animals that fed from the Grierson Dump, sparking a new debate over its impact. The city stopped allowing slops to be dumped but didn't ban anything else.

Finally, in 1917, there was a push to change how the city dealt with its trash. Aside from floating the idea of cooking garbage (which was thought to make it less likely to poison pigs and other livestock), Edmonton introduced a system to collect waste from homes. The same year, the mayor developed a plan that would see the city pay people to bury the trash in Grierson Dump to reduce the problems.

Despite these plans, as well as years of protest and petitions from nearby residents, Grierson Dump refused to disappear. As the city's population grew, so did the dump into the 1920s and 1930s. The Great Depression spurred a new wave of people to sift through the city's waste, looking for anything valuable to sell. A 1937 feature by the Edmonton Journal found one recent immigrant who made a decent living in the shantytown by turning trash into flower pots and other items.

But the dump's days were numbered. During that decade, the city had made many attempts to finally close down the Grierson Dump and repeatedly tore down the homes of the 60-odd residents who lived there. But the shanties would be rebuilt just as quickly. Finally, in 1938, the city made a final strike against the dump by evicting the residents and bulldozing anything that stood on the grounds.

The dump would sit idle as an abandoned trash pile for years. Then it became a Chinese market, a parking lot, and, eventually, its current form: Louise McKinney Park, which opened in 2008.

Waste disposal remains a big issue for Edmonton, although the times of just chucking everything into the river valley are thankfully long over. In the past year, the city has launched multiple new waste initiatives — some more controversial than others — including collecting food scraps from apartment buildings and reducing single-use bags and other items.

This is based on a clipping found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist @revRecluse — follow @VintageEdmonton for daily ephemera.