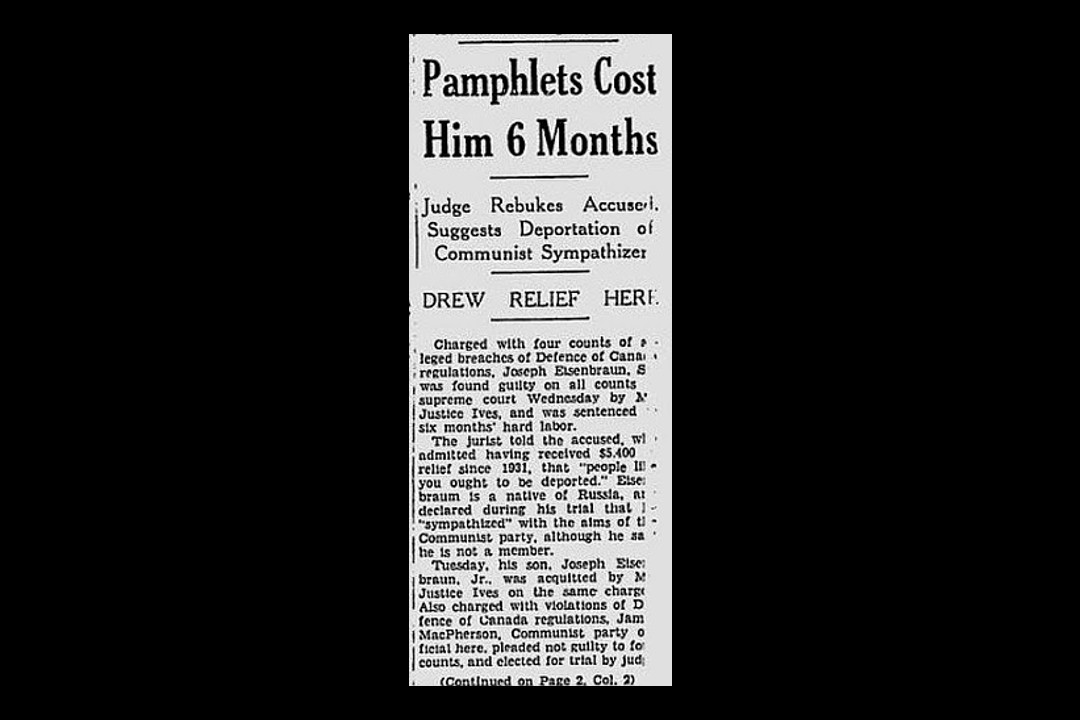

On this day in 1940, an Edmonton man was sentenced to hard labour for passing out communist literature.

Joseph Eisenbraun Sr. was found guilty of breaking the Defence of Canada regulations, which were brought into effect under the War Measures Act in 1939, right before the country entered the Second World War. The act gave the government extraordinary powers to censor newspapers and radio broadcasts, and to detain anyone who acted "in any manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the state."

In Eisenbraun's case, he received the pamphlets from a man on 96 Street, who offered him six copies to sell to others. Eisenbraun claimed he only sold one, which unluckily happened to be to a detective. The newspaper account doesn't detail what was actually written in the pamphlets (Eisenbraun argued that he didn't "read or write" much and didn't know what they said).

What is clear is that whatever was written on the pamphlets was enough for a judge to label the defendant a "Communist sympathizer" and openly wish he could deport Eisenbraun, a naturalized citizen, back to his native Russia.

Eisenbraun's trial is one of the most striking examples of the anti-communist sentiment that spread through Edmonton (and Canada) at the time. The city had a history of labour activism. Eisenbraun's trial was less than a decade after the Hunger March of 1932, where thousands of people protested to demand changes in the face of increasing poverty and starvation during the Great Depression. Many of those present were involved in communist-supported or aligned organizations, and then-Premier John Brownlee would later claim that "communist propaganda" and not true need were behind most of their demands.

Anti-communist sentiments continued as the war progressed. In 1940, Canada banned about a dozen organizations, claiming they were a detriment to the war effort. While some were said to be aligned with fascism, many were left-wing labour organizations. Among them was the Communist Party itself.

Cases like Eisenbraun showed the government's attempt to crack down on communist ideology, but much of the so-called "Red Scare" in Edmonton came from unofficial sources. Anything that leaned too far into supporting union organization, or anti-war sentiment, risked being labelled as communist propaganda. Take the Chocolate Bar Strike of 1947, which saw hundreds of Edmonton children take to the streets, joining other movements nationwide to protest the rising cost of chocolate bars (going up from five cents to eight.) The protests gained momentum, only to fizzle out after newspapers began claiming the children were being secretly manipulated by communist agitators (for who else could convince children to be passionate about chocolate?)

The federal government lifted some restrictions on speech at the end of the war, but Alberta's provincial government continued attacking what it saw as subversive ideologies. Premier Ernest Manning and the ruling Social Credit party were loudly anti-communist. In 1946, they expanded Alberta's powers to censor films primarily to "eliminate communist thought from Alberta-shown movies." Manning was also quick to label union organizations and potential strikes as being the work of communists eager to sabotage Canadian productivity. These sentiments weren't just empty political rhetoric — they were used to reduce union support, allowing Manning's government to weaken worker strike protections.

Accusations of communism might not carry the same heft they did in the 1940s and 1950s, but the tactic hasn't completely disappeared as a way to dismiss a political opponent, regardless of whether the label fits or not.

This clipping was found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist @revRecluse of @VintageEdmonton.