South Edmonton’s surprising deer paradise

Mel Priestley explores how a herd of whitetails came to live on a patch of land surrounded by city

The doe moves along an open field of grasses near the edge of a cattail pond, grazing slowly. Beside her, a buck stands motionless underneath the broad branches of a poplar tree, his antlers burnished gold in the late afternoon sunlight.

It’s an idyllic scene, but it’s not from a national park. It’s right in the middle of south Edmonton. While the deer are grazing in a semi-natural green space, they are also standing behind chain-link and barbed wire, close to the large industrial buildings within the fenced-off area that houses the AltaGas Edmonton Ethane Extraction Plant (EEEP). The area is flanked by the massive development of South Edmonton Common and the city’s southern residential sprawl, and ringed by the busy commuter routes of 23rd Avenue and Gateway Boulevard/Calgary Trail.

It’s a mystery in plain view: How have so many deer managed to survive – and even thrive – in such an urban area, and is their presence here safe – for both the deer and the city’s residents?

South Edmonton's surprising deer paradise

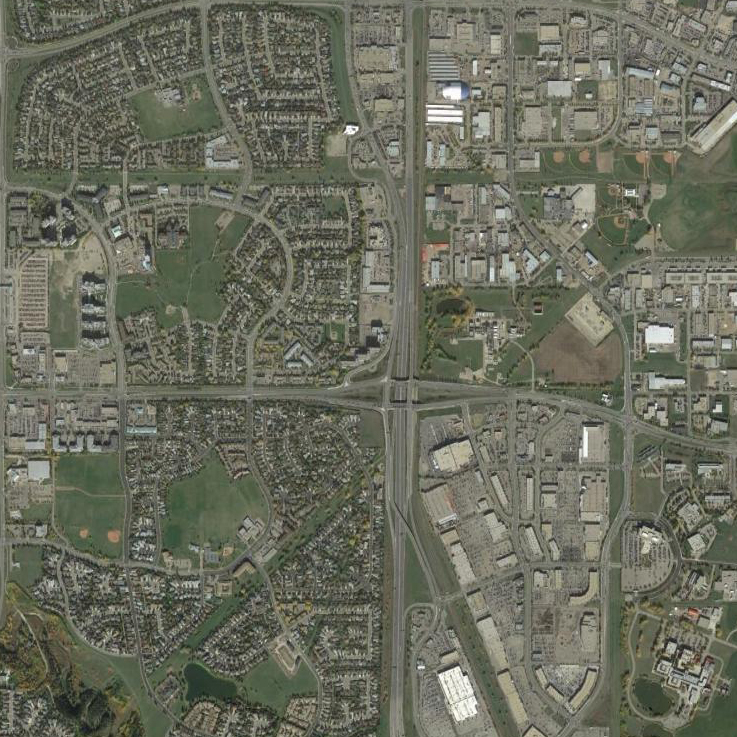

Click on the icons to learn more about the area in south Edmonton where a herd of whitetail deer has been living for years.

Home on the range

The deer are well-known to those in the area. Google “Edmonton Ethane Extraction Plant” and the first image result is a group of six deer standing in the snow on the other side of a chain-link fence. Commuters along the freeways often spot the deer from the road. The employees at the plant are the most familiar with the deer, since they’ve been a continual presence on that land since the plant was built in the late 1970s — back when the area was very rural and surrounded by farmland.

Daryl Matter, co-ordinator of maintenance management at the EEEP, is called the “Deer Whisperer” by one of his colleagues because of the special attention he has paid to the animals over the 40 years that he’s worked at the facility. “I sometimes bring them little treats to eat,” he says over the phone.

Sidebar: Should we feed the deer?

There are eight deer on the EEEP land right now, says Matter. They do leave and enter the area, at least occasionally. He points to the green corridors that run both northeast and southwest of the facility’s area, which correspond to a pipeline running from the EEEP through the city, as their most likely route. To the northeast, the corridor extends up to the Mill Woods Golf Course and the ravine adjacent to that; to the southwest, it runs all the way to the Blackmud Creek Ravine.

The number of deer at the EEEP has stayed fairly constant over the past couple of years, Matter has observed. He has seen them exit and enter through the plant’s access gates when they are left open during busy times. Neither he nor any of the other employees have seen a deer jump the fence, and while he acknowledges that they certainly might do this, the height of the fence and its barbed wire topper makes that seem unlikely, unless the animals were under serious stress.

“They couldn’t find a better place to be in, as far as protection from predators, because they really have no predators here,” Matter says. “They’re fairly well protected here. I think they’re happy!”

An urban heaven

Indeed, by all appearances, the EEEP’s land is a veritable deer paradise.

“It really pops out as a perfect little refuge,” Colleen St. Clair says. “You couldn’t really draw a picture that is more attractive to deer than that little plot on the west side of the plant.”

St. Clair is a professor of biological sciences at the University of Alberta and has worked extensively on urban wildlife. She heads Edmonton’s Urban Coyote Project, a study that collects information on coyote movement, habitat selection, diet and disease. She was previously involved with Edmonton’s Urban Deer Project, a student-run research project that gave undergraduates field experience in research methods while gathering information about deer movements and habitat in the city.

Studying satellite imagery on Google Maps as she talks, St. Clair notes that while it might seem unusual for deer to be so far into the city, they aren’t that far away from the Blackmud Creek Ravine — an area with a high concentration of deer. She finds it unlikely that the deer would spend all their time on that piece of land. That area is simply not big enough to support a large deer population on a permanent basis, she says, and agrees with Matter’s speculation that the deer are most likely using the green corridors extending out from the EEEP as paths in and out of that area.

“They are amazingly good at slipping in and out of places under the cover of darkness,” she says. “I would be very surprised if they are stuck in there and can’t leave. It might look that way from the roadside, where you’re looking through a fence at them. … Our vantage from the road is often really different from the animal’s vantage at ground level in the way that they move. It wouldn’t be that hard to cross Calgary Trail there — in really early hours of the morning is probably when they do it.”

The deer are behind a fence, but they likely leave the property from time to time, says wildlife biologist Colleen St. Clair. "I would be very surprised if they are stuck in there and can't leave." (Deer photos by Mack Male)

But there’s also evidence suggesting that the deer spend long periods of time on the EEEP land without leaving. When they do leave, they may travel all the way to the ravines, or they may stay on nearby green spaces.

“My assumption would be that unless there was some reason for them to leave, that they would probably spend their time there,” says Emily Herdman, a wildlife biologist with Alberta Environment and Parks. “There [are] a lot of deer that live in fairly urban environments. It isn’t unheard of, for sure. And as long as they have the things that they need, and there’s not a specific stressor or source of mortality, then there’s no reason why they would leave.”

She verifies that the Alberta government didn’t put the deer there, as some anecdotal reports have suggested. “We don’t have any record of moving deer onto that property, and we’re usually quite good about keeping records about that kind of thing,” she says.

Deer are a common sight to the employees of the Animal Medical Centre on 23rd Avenue and Parsons Road, tucked into the southeast corner of the same parcel of land as the EEEP. Veterinarian Peter Claffey and his staff have seen the deer on a weekly basis since the clinic was founded 20 years ago, back when the area to the south was all farmland. Claffey recalls seeing a single deer in the EEEP’s fenced-off area right after the fence was installed; he assumed it had been trapped. It was quickly joined by others. The second appeared injured, he remembers, though it soon recovered.

“Right now there’s enough property in there to supply them,” Claffey says. “They’re really a healthy-looking herd of deer.”

Clinic staff have seen as many as a dozen deer in the area, and that it does seem to fluctuate occasionally, Claffey says. However, they only see them about once a week, as the animals usually congregate away from the clinic, in the northwest part of the area near the pond. Coyotes are more of a concern to the centre, he explains, and that’s why they have their own fence surrounding the yard. Still, occasionally he does notice interactions between the deer and other local animals.

“[Sometimes] they’ll come over here, especially when they get into the breeding season — they’ll come over here and sometimes they chase cats,” he says with a chuckle, referring to the pets and strays in the neighbourhood. “They’re fun to have around; I enjoy watching them.”

The deer seem very healthy, says veterinarian Peter Claffey, whose clinic gives him a great view of the herd.

Deceptive danger

Chance encounters with urban wildlife can be exciting, though they can be unsettling or even dangerous as well. Deer aren’t the safe, cuddly creatures that they might seem to be on first glance.

“Deer are a much bigger threat to the security of people in cities than coyotes are,” St. Clair says. “If people have some doubt about what deer can do to pets, they should Google that and watch a few YouTube videos. It’s astonishing how aggressive deer can be towards people and pets.”

Yet there’s a notable absence of stories about urban deer, while stories about urban coyotes have increased. Various local news media sources have reported on urban coyotes within the last couple years, usually spurred by an attack on a pet (often an off-leash dog) or sightings in residential areas.

The perception that herbivores are less threatening to humans than carnivores is very common, notes Rob Found, a wildlife biologist who focused on urban deer during both his undergraduate and PhD work at the U of A.

“In my opinion, the threat of coyotes tends to be exaggerated — as it is with most predators — and it tends to be possibly downplayed when it comes to the non-predators, the herbivores like deer,” he explains. “Deer can actually be quite dangerous if you run into them; they could still kill a dog. … They get hit [by cars] a lot more than coyotes, so the risk on the roadways is greater with deer as well.”

Found estimates there are about 300 deer in Edmonton, the majority of which are white-tailed deer (including the ones on the EEEP land). White-tailed deer are usually less aggressive than mule deer, which are usually the species involved in incidences of aggressive behaviour. Found bases this information on research he conducted a few years ago at the U of A, which included both GPS tracking and collecting deer droppings. He focused particularly on deer-vehicle collisions in the city and published two papers in 2011 on the subject: one predicted where such collisions would occur in Edmonton, and the other measured the effectiveness of warning signs in mitigating deer-vehicle collisions.

One of the hotspots identified by Found was near the Blackmud Creek Ravine. The area along 23rd Avenue near the EEEP, however, wasn’t a hotspot then, and it doesn’t seem to be one now. Between 2006 and 2016, the city recorded only four animal-related collisions on Gateway Boulevard between 19th Avenue and 23rd Avenue, and only one of those reports mentioned deer specifically. In an email, Edmonton’s Animal Care and Control Centre confirmed that three Kennel Care Staff recall having calls about deer carcasses in the 23rd Avenue area in the past, but since the area’s urban development those calls are now rare; they are much more likely to get calls about coyotes and rabbits in that part of the city.

These numbers suggest that the deer on the EEEP land tend to stay there for long periods of time, as both the plant’s employees and others have suggested, or they’ve become adept at crossing busy roads safely and inconspicuously.

1982

2015

Then and now: An aerial image of the area in 1982 compared to the same view in 2015.

Disappearing boundaries

Urban sprawl constantly displaces wildlife from their habitats, changing the ways in which animals and humans interact, sometimes radically so. As neighbourhoods creep ever farther from the city centre, the well-defined boundary between urban and rural has largely disappeared. Instead, there’s now a gradual transition from suburbs, with houses close together, to larger homes on bigger pieces of land interspersed with wider green spaces, and then acreages and farms beyond that. That landscape creates conduits for wildlife to easily enter and exit cities.

While the deer on the Edmonton Ethane Extraction Plant land are an oddity, St. Clair believes that similar situations may not be far away.

“I think it’s going to get more complicated in Edmonton,” she says. “Climate change is going to mean — especially with winters like this last one, much milder winters — it’s going to mean the habitat in and around Edmonton becomes more supportive of deer populations. As they become denser in their areas, they’re going to expand a bit more into the less desirable areas.”

Photos courtesy of Mack Male, Alberta Environment & Parks Aerial Photos, and Google Earth.

Written by:

Tagged: