Taking a bite out of food waste in Edmonton

Hungry for change? We need to educate ourselves to take action

We share, we gift and we eat during the holiday season. Those close family gatherings and catered work parties are infused with an abundance of food, good conversation and shortbread. Food drives, hosted holiday meals, and donations to Edmonton’s Food Bank are also in full swing to support the less fortunate in our city at a time more difficult than most for those struggling to support themselves. The stark imbalance between the two scenarios is disconcerting; a truly uncomfortable feeling cast in an unfavourable light when considering how much perfectly good food goes to waste after the festivities are over, the lights are turned off and everyone goes home.

What is food waste and how big is the problem?

Food waste is discarded or uneaten food, lost along various stages of the value chain, from production to consumption. Though we often conflate food waste and food security, they are different. Food security means all people have a right to nutritionally adequate and safe food, made accessible via social and economic support. Both challenges are being addressed on a global scale as communities work to find solutions and create action plans.

Each year, food waste in Canada totals $31 billion. To put that in perspective, almost 40 percent of all food produced, or 2 percent of Canada’s GDP is thrown away, which translates to a swift uptick in food costs at the consumer level of 10 – 20 percent. According to a recently completed study on food waste by IMC (Ian Murray & Company Ltd.), commissioned by Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Canada “generates more municipal waste per capita annually than any of its peer countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperating and Development (OECD).” Within Canada, Alberta outranked all other provinces and territories as the leader in food waste per capita (pg.6).

The report goes on to state we are “far behind” other countries like the US and much of Europe in finding a cohesive and effective way to approach the issue. In fact, IMC reported that although experts agree escalating food waste volumes are one the most pressing issues impacting the environment, “there is no clear commonly agreed on definition of food waste in Canada and therefore no common measures of food waste and its impact on businesses and the environment.”

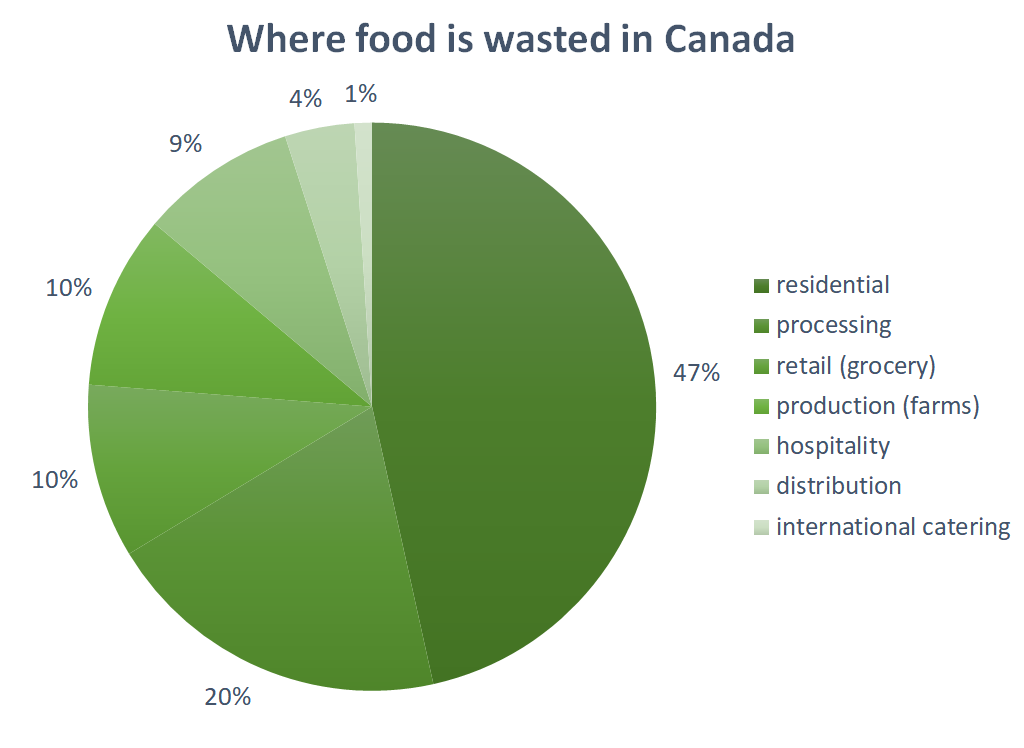

Here’s how food waste distribution percentages are broken down along Canada’s food value chain, according to IMC’s May 2017 report:

- Nearly half – 47 percent – of waste is attributed to consumers (residential);

- 20 percent of waste occurs in the processing phase;

- 10 percent of waste is attributable to retail stores (grocery);

- 10 percent of waste occurs at the production stage (farm);

- 9 percent of waste can be blamed on the retail industry (restaurants, hotels);

- 4 percent of waste occurs during transit (distribution);

- and 1 percent of waste is attributable to international catering waste

What happens to food waste in Edmonton?

Currently, the city diverts over 50 percent of residential waste from the landfill by recycling and composting; the organic material separated for composting once it reaches the Edmonton Waste Management Centre. Significant as this number seems, Edmonton’s approach doesn’t have any discernable effect on consumption habits, unlike programs where citizens sort their own waste prior to using municipal waste disposal services.

There are groups in Edmonton that are trying to tackle the issue of food waste earlier in the process, however, as well as a few City-led initiatives that are underway:

- Edmonton’s Food Bank is the city’s most established emergency food recovery organization, with an estimated 4.2 million kilograms of food gathered and redistributed in 2016 alone

- OFRE (Operation Fruit Rescue Edmonton) aims to establish urban, local connections with food and will take surplus fruit from local growers or aid in the harvest of excess fruit crops and donate to various charitable food organizations

- Fruits of Sherbrooke also rescues fruit locally grown, their strategy based on connecting, teaching, and making

- fresh: Edmonton’s Food and Urban Agriculture Strategy focuses on creating “a resilient food and agriculture system” that contributes to the overall sustainability of the city and includes “treat food waste as a resource” as one of its nine strategic directions

- Leftovers YEG focuses on food recovery and advocacy, redistributing food from commercial sources to various agencies in need

Inside Edmonton's Food Bank

How does Leftovers YEG work?

Leftovers, a Global Shaper’s initiative based on one of the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals, first launched in Calgary in 2012. Seeing how much food waste occurred at the retail level, and feeling shocked at how much waste Alberta generated overall, they decided to get involved.

“We found a gap with small vendors that the Calgary Food Bank couldn’t get to, and we reached out. They actually put us in touch with smaller vendors and said ‘it would be a huge help if you guys could fill the void,’” says Lourdes Juan, founder of the Leftovers initiative.

The relationship with the local food bank has worked out well, as Leftovers directly delivers food to them, as well as various other agencies with need. “We didn’t want to compete, but support them,” she says.

Impressively, Leftovers Calgary can now also count Uber, who recently committed to donating 40 rides per month for volunteers rescue routes so that vehicle ownership is not a hindrance for those intent on helping, as a partner. They are also hoping to establish a relationship with large-scale retailers like Walmart to creatively circumvent logistical challenges and prevent food waste.

By the looks of the extensive list of partnerships Leftovers has acquired, it is no wonder that they’ve managed to rescue over 75,000 kilograms of food to date. And the numbers keep growing as they search for new creative avenues to rescue food.

Leftovers YEG volunteer Alex working

In Edmonton, Juan sees an opening for Leftovers YEG to focus not only on redirection efforts, but also on advocacy and public educational opportunities. “I believe positive food consumption education can be adopted young, leading to lifelong habits that help, rather than hinder, the issue,” Juan says, and believes this style of interaction encourages community engagement, which ultimately has a positive impact on shaping policy to support these initiatives.

Still, collaborations with other agencies in Edmonton need some work, Juan concedes, “Leftovers YEG needs some room to grow up and see where that takes us.” She feels conversations need to be had with local Edmonton agencies to assess their unique needs and fill the void, whatever that entails.

What stops these programs from being more effective?

New startups like Leftovers YEG face a number of practical hurdles, including regulations, funding and the sheer volume of accessible product (both perishable and non-perishable). Beyond that, it gets complicated. “The issue of food security isn’t just about rescue and redirection,” says Juan. “Those are more reactionary, band-aid solutions to the wider issue.” She implicates income levels and food access as larger culprits in a massively complex problem, which is why she feels we need to dig deeper.

Food safety

Although residential waste accounts for 47% of total food waste in Canada, food safety regulations make it difficult to initiate food recovery/redirection efforts from homes. Alberta Health Services (AHS) regulations state that the more contact food has with human beings on the production level, the higher-level risk it is assigned. Many retailers fall into either medium risk or high-risk categories, with full-service restaurants, caterers and food manufacturers all designated high-risk. AHS prohibits residential door-to-door food recovery, so the only residential options involve composting and biofuel sites.

How freshly prepared food is transported and the temperature that must be maintained to ensure food safety requirements are met is also crucial. If the route takes too long and temperatures drop out of an acceptable range, or the recipient agency doesn’t have the facilities or capacity to properly store the food, it must all be thrown out.

This is precisely the reason Leftovers says that food is best donated in its most raw form. Grocery stores make ideal donor partners because of this and are listed as a low-risk by AHS, but ironically, large-scale grocery retailers are some of the hardest sells when it comes to agreeing to donate.

Logistics

Beyond jumping through all the red tape and regulations associated with operating a not-for-profit organization, managing route schedules and the constant challenge of finding (and keeping) volunteers, agencies like Leftovers have learned to expect the unexpected.

Perhaps a vendor donated less or more than originally communicated, and now volunteers must scramble to find multiple agencies who will take the food if the intended one has less storage space and capacity to utilize the over/under abundance as initially thought. Perhaps a vendor donates all bakery products one week when a particular agency needs milk. The list goes on.

Furthermore, using large-scale retailers as an example, most do not want to allocate dedicated staff to glean, package and track donated food. Beyond the financial implications, large-scale retailers also cite “inadequate refrigeration/storage on sites, transportation constraints and regulatory concerns,” which translates into an overarching concern about liability.

Income Scarcity and Food Access

A monumental topic for discussion in and of itself, an Avenue Calgary article points out that in 2011, “12.3% of Alberta households experienced food shortages due to financial constraints.”

Homelessness is also mentioned as one of the greatest logistical challenges related to food access, and Juan, who serves on the board of directors for the Calgary Homeless Foundation, says she and her team are strategizing currently on how to tackle the complexity of this issue through Leftovers Calgary and YEG, and how they might be able to utilize the fluidity of their organization to make a difference.

What are Edmonton’s current goals related to reducing food waste?

The Edmonton Food Council (editor's note: Taproot Edmonton co-founder Mack Male is an active member as of 2017) was established in 2013 to support implementations of Edmonton’s fresh initiative, and though it would seem the city is abuzz with local activism through active public engagement, not to mention we have a state of the art waste management system, implementation at the policy level has proved challenging.

Our goals, according to the city’s website, are to achieve 90% residential waste diversion from landfill, but that doesn’t refer to food waste specifically. A timeline has not been set, with public engagement deferred until sometime in 2018. Goals for commercial food waste diversion are not mentioned. Calgary on the other hand, has established the specific target of aiming to divert 70% of all municipal waste from the landfill by 2025, revised from an earlier target of 80% by 2020.

Edmonton Waste Management Centre

What could be done at the policy level?

“Food has always been an integral part of city building, and yet we don’t see food as integral to city functioning as, say, infrastructure,” says Kathryn Lennon, Principal Planner for fresh: Edmonton’s Food and Urban Agriculture Strategy.

To form policy that adequately addresses the issue of food waste and its connection to food security, a definition and baseline understanding of how to properly track and quantify data collected is required. As Lennon notes, “we’ve got a lot of anecdotal information, but no solid understanding of context for Edmonton.”

Lennon goes on to say that, “we don’t really understand [yet] how a city can be involved in food growing, food access, and security. We don’t understand the role of the city in the whole security discussion.”

There are some avenues to pursue policy-wise that could open up doors for further conversation, as well as pave the way for more food specific strategies to combat food waste. By piloting the Vacant Lot Cultivation Licence, for example, the city can utilize land use agreements to make temporarily vacant, idle, and underused City-owned lots available for food production. By establishing new land use classes such as Urban Outdoor Farms, Urban Indoor Farms, and Urban Gardens, the city can foster the resiliency model outlined in fresh.

With these policies specifically, there is a potentially significant public engagement opportunity to educate and inspire citizens to grow and cultivate their own produce rather than purchase, which addresses the topic of induced demand along the food supply chain outlined in the IMC report. This ties into the bigger picture, as Marjorie Bencz, Executive Director for Edmonton’s Food Bank says, “a big barrier [to people accessing food] is not having adequate housing or income.”

She feels lack public awareness of the issue is creating a gap in being able to adequately address food waste in Edmonton, and sees the need for advocacy as a major component of targeting the causation of security issues. A sobering survey the Food Bank carried out in 2015 of some 400 clients revealed that the level of need went well beyond simple access to good food and sparked a new collaboration with various local organizations to provide educational opportunities around issues such as budgeting, basic self-care and food preparation.

Specific to regulatory policy, some interesting approaches were suggested in the IMC report, and some groups have seen varying degrees of success based on these approaches.

- Municipalities can implement higher tipping fees to de-incentivize large-scale retailers from using city disposal services for food waste

- Addressing improper coding of best before and expiry dates on grocery shelves (a significant cause of food waste both on and off the shelf), and educating the public on the difference between the two can significantly cut down retail and consumer waste

- Enacting a zero waste policy for large-scale retailers, by forcing them to adopt strategies to donate all unused or “imperfect” food will substantially cut down food hauled off the landfill and meet an important social need in the process

- Establishing a composting program in which citizens sort their own waste in different bins prior to using waste disposal services, more residential waste can be directed to biofuel and composting facilities, which would significantly cut down on GHG emissions

- Incentivizing large corporations, agricultural operations and other retail businesses to donate food by allowing tax deductions for charitable contributions, eases the financial aspect of logistical challenges to donate

- Protecting food donors through legislation such as the Charitable Donation of Food Act reduces fear of liability risk, enabling cooperation of large-scale retailers such as grocers

What lessons can we take from elsewhere?

Global commitment to the principle of zero waste is gaining steam, which experts believe provide solutions to combating climate change, creating resilient communities, and addressing food security.

It’s a good thing too; organic food waste, according to the OECD, is expected to double within the next 20 years.

According to the IMC report, in 2013, the EU said it would reduce food waste 50% by 2020, “providing a focal point and rationale for an array of actions,” for OECD members to abide by and emulate. The goal, which is more ambitious than the United Nation’s original target for SDG Goal 13, either directly or indirectly influenced the following initiatives:

- Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia are touting tax incentives to prompt food producers to donate

- Manitoba aims to become a zero-waste province, and committed to reducing waste per capita by half by 2020

- Halifax imposed an organic disposals ban

- Vancouver and Nanaimo also imposed an organic disposal ban

- Vancouver and Toronto launched consumer awareness campaigns aimed at reducing food waste

- Love Food Hate Waste initiative aimed at consumer education was launched by the Waste and Resources Action Program (WRAP-UK)

- France used legislative means to ban food waste by grocers, requiring them instead to donate to food banks and other agencies in need

- Spain is also experimenting with banning food waste and gleaning efforts, but offered a tax incentive for donations to retail grocers

- The United States committed to a goal of reducing food waste by 50% by 2030 through a collaborative effort by an organization called Rethink Food Waste through Economics and Data (ReFED)

- Australia has adopted a similar strategy to the EU

- Hong Kong aims to reduce its waste by 40% by 2022

These are just some of the bold initiatives gaining traction, and attention, domestically and globally. They require a strong level of commitment and collaboration across governments and agencies to legislate. Organizations such as Food Secure Canada are advocating to enable smart food policy, to create a consistent definition of what food security in Canada looks like and how cities intend to combat it in their own backyards.

What does this mean for food waste in Edmonton?

The IMC report, which is directed at Calgary and Edmonton, points out that, “several options exist at the policy level to influence education and production in the effort to reduce food waste nationally, but once the supply chain is activated, options are limited to recovery and diversion tactics.”

This suggests that the solution for Edmonton requires a focus on cultivating the right attitudes about food waste, in addition to solving access issues. The importance of the issue is clear, but we must truly understand its complexity and how we’re contributing to the problem if we’re going to effect positive change and reduce our waste.

We can’t just patch a hole in the bucket with tape; our responsibility doesn’t stop once we’ve donated to the Food Bank. Residential food waste is the biggest contributor to Canada’s overall waste problem, and requires us to engage our social conscience and take action where it matters; at home.

As a city, we can’t implement structurally sound policy without the solid foundation a good definition and baseline would provide. We need this baseline to contextualize our goals so efforts to combat food waste aren’t stalled in perpetuity, with no real substance established or social gain achieved.

What can you do to help?

As individual citizens, we can:

- Lobby our local government representatives to ensure timelines for public engagement initiatives on the future of food waste in Edmonton is adhered to and hold them accountable for developing policies, such as higher tipping fees to de-incentivize large-scale retailers from using city disposal services for food waste and addressing improper data coding of best before dates on the grocery shelves (a significant cause of food waste both on and off the shelf), to address the “bigger question”

- Educate ourselves on how we can compost our own residential food waste to divert it from landfills

- Volunteer with a recovery agency – remember: citizen-led advocacy leads to real, meaningful change in Edmonton

Photos courtesy of Mack Male, Michelle Taylor, and the City of Edmonton.

Written by:

Tagged: