Forces that drove Edmonton’s car city mentality - and how to steer into a new direction

Some say Alberta’s capital is in the same situation as other North American cities

By Stephanie Dubois

Edited by Therese Kehler

Go for a stroll through an Edmonton neighbourhood and you’ll likely come to the conclusion that many others have reached: Edmonton is a motor city, a place where pickup trucks and cars rule the road.

It wasn’t always like that. So how did we become a city that caters to vehicles first?

It begins with urban planning. Like many North American cities, the car’s dominance on Edmonton roads grew as the Prairie city’s boundaries crept ever outwards.

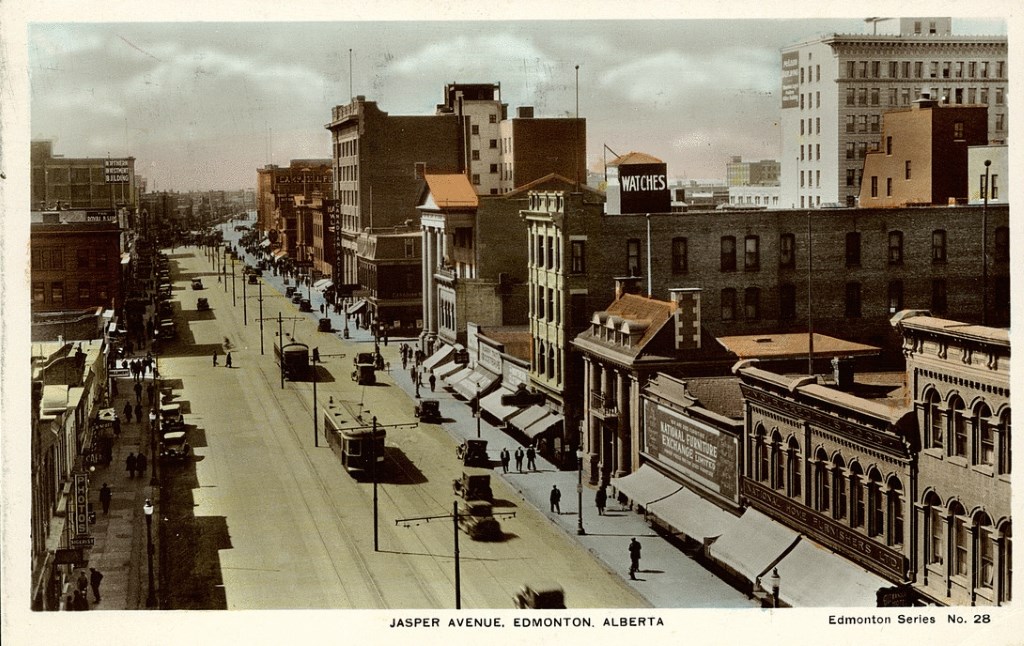

A historical bird’s eye view of Jasper Avenue. Credit: University of Alberta Libraries

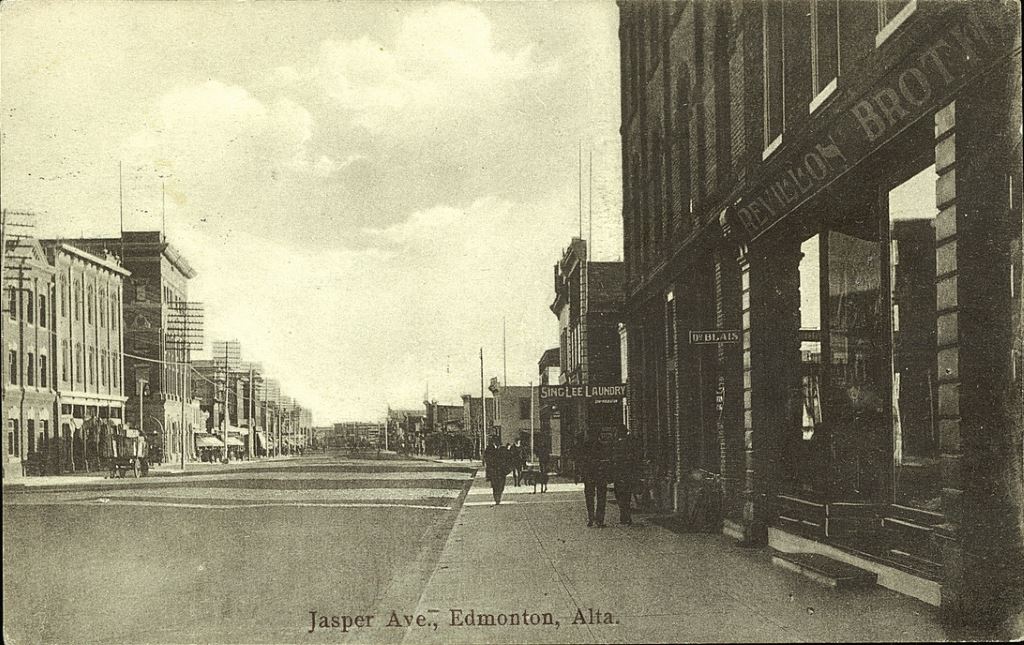

It started in the 1800s when the Hudson’s Bay Company created the Edmonton’s grid road network for wagons and pedestrians in the settlement, says Shirley Lowe, a former Edmonton historian laureate and author of a June 2018 report called Edmonton’s Urban Neighbourhood Evolution.

In 1908, the first streetcars were running in Edmonton as residents began moving away from downtown area. The streetcars were reliable and well-used by residents; by 1912, the streetcar lines extended between 75th and 124th Streets, north to what is now Yellowhead Trail and south across the river to the newly amalgamated Strathcona.

A photograph of Jasper Avenue in 1910. Credit: University of Alberta Libraries

In 1914, the growing city adopted a new numbered system for its roadways, “with only a few main streets keeping their original designations,” according to the website Edmonton Maps Heritage.

At the same, the car’s popularity was growing — and fast. According to the Alberta Motor Association, there were 41 car owners in 1906 and a whopping 29,000 licenced drivers in 1918.

“The last streetcar in Edmonton stopped running in 1951,” Lowe writes in the Neighbourhood Evolution report. “The Postwar era began its love affair with the car.”

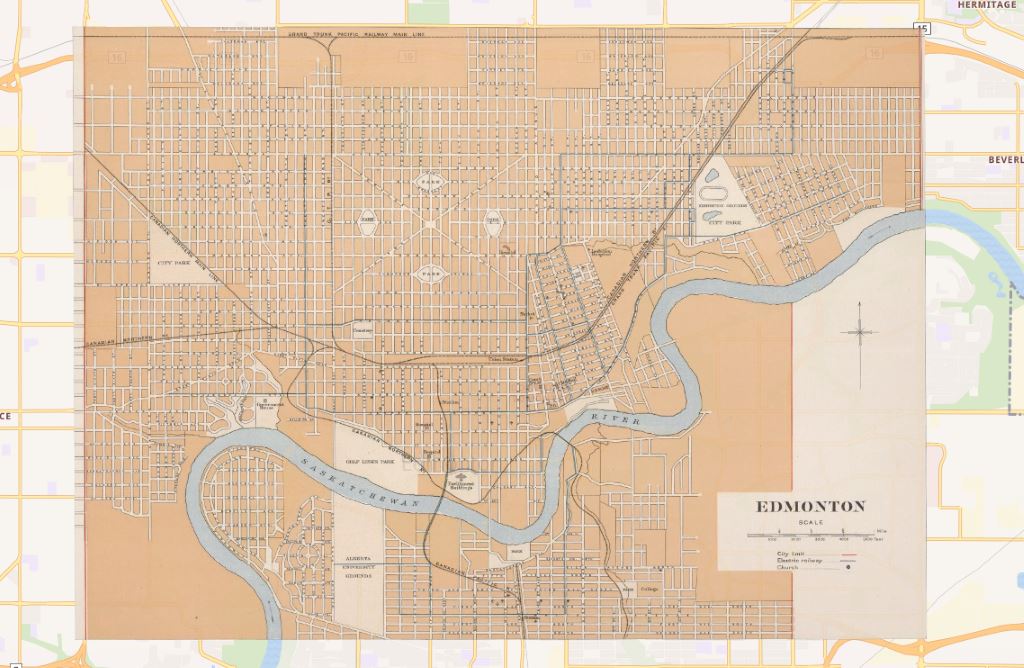

This shows what Edmonton looked like in 1915 overlayed with Edmonton’s current Google map. Click here for an interactive version. CREDIT: David Rumsey/Geofencer.com

The end of the Second World War in 1945 ushered in a period of renewal and major growth in Edmonton, from the discovery of Leduc Number One to the start of the baby boom. In 1949, the city hired its first planner who introduced a strategy of planned neighbourhoods, in which Edmonton’s housing developments would be protected from the hustle and bustle of busy roads.

Say goodbye to what was known as the “gridiron pattern of blocks” in Edmonton. And say hello to the modified grid neighbourhood.

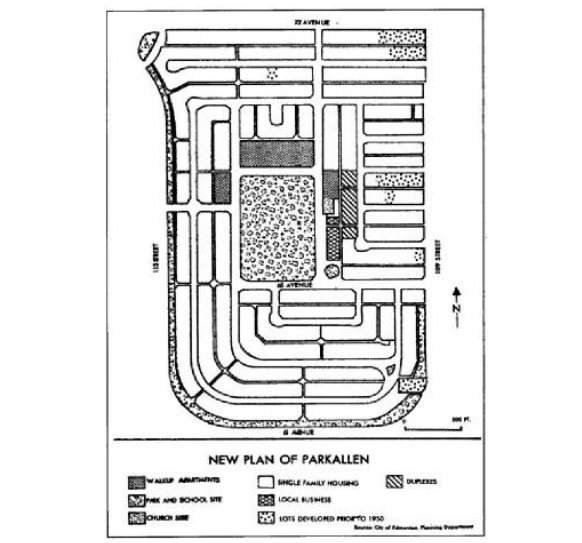

“The perfect neighbourhood would have a modified grid and accommodate 15,000 people, a residential area of mixed density, no through traffic, park space, central services and a school,” explains the Neighbourhood Evolution report.

Commuter roads were ringed around residential communities to reduce the number of vehicles short-cutting through them. In 1951, Parkallen was the first community in Edmonton to be designed in this manner.

“The modified grid didn’t have many ways in or out. You had one road that took you in,” Lowe says.

Eventually used in more than 40 neighbourhoods, the modified grid was effective in calming traffic but it was also a significant milestone in favouring cars over pedestrians. “They basically kicked the pedestrian to the curb and you had to walk around in circles,” says Lowe. “This was all about making it easier for cars and containing some of the traffic.”

The development plan for Parkallen, Alberta’s first planned neighbourhood. CREDIT: “Edmonton’s urban neighbourhood evolution.”

In 1963, the city adopted its first municipal plan. In it, the urban planning concept called suburbia emerged and Edmonton adopted the new, predominantly American way of life.

Neighbourhoods drifted away from the downtown core and freeways were developed, explained Lowe.

But many Edmontonians at the time didn’t love the idea of major highways in the city. Lowe calls this the start of an anti-car movement. But it didn’t get far, she says, because there were so few alternatives.

The car quickly became an important part of everyday life for Edmontonians and played a huge role in the economic development of the city, Lowe says.

The post office on 100th Street, taken circa 1940-1960. Credit: University of Alberta Libraries

Traffic engineers had to find ways to expand the road network to include more vehicles. New highways and arterial roadways within cities were created to move cars through Canada’s urban landscapes, according to Understanding Sprawl: A Citizen’s Guide, published in 2003 by the David Suzuki Foundation.

With that came a glut of cars and no infrastructure to support other modes of transit.

“Most of these new residential suburbs were planned almost entirely without public transportation. There were often no sidewalks, and curvilinear streets ending in cul-de-sacs replaced the grid pattern of the old cities,” writes David Gurin, the report’s author.

“As a result, transportation planning became mostly a matter of providing additional road capacity. Canada’s transportation system became, in large measure, an automotive system, rather than a balanced system that integrates the use of cars, buses, streetcars, and railroads, with allowance for safe walking.”

You go to work, you drove your car. Have more than two cars at home? You’ll need a bigger house with a bigger garage.

“We had a baby boom and then the car was becoming something you had to have,” Lowe says. “Everything that happened involved the car industry: drive-ins, road trips, owning RVs, it just exploded. You could never catch up with it. Even now.”

Some argue very little has changed since then.

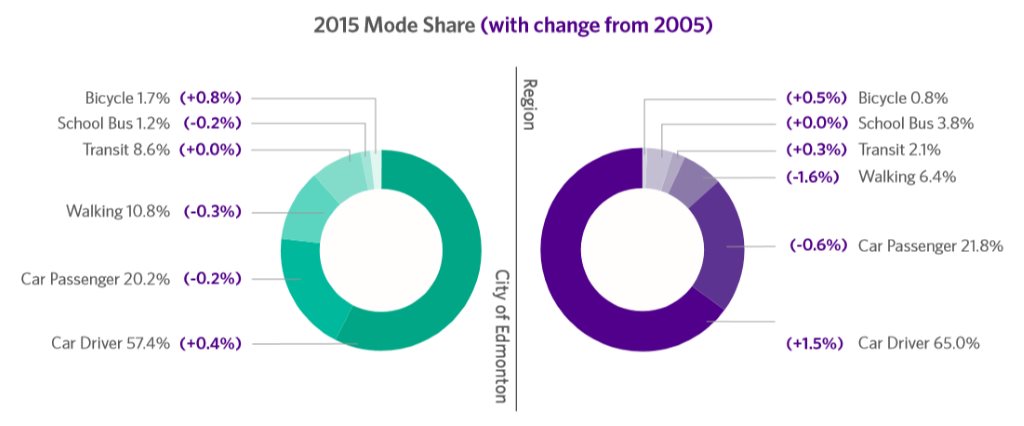

City census data from 2016 shows that 72 per cent of those surveyed used a vehicle to get to work from home. The 2015 Edmonton and Region Household Travel Survey also showed the dominance of vehicle commutes, accounting for 78 per cent of trips of those surveyed.

But that growth is putting pressure on the city’s finances.

Mayor Don Iveson has said the city simply can’t afford to keep up with the growth in newer neighbourhoods and the financial requirement for twinned roads and upgraded interchanges.

One of those examples includes the Whitemud Drive interchange upgrade in southwest Edmonton that has been floated for three decades. Continued growth in the Terwillegar area has left commuters with traffic headaches during rush hour and politicians debating the best way to get people out of that area quicker.

In October, city council opted instead for an expressway that will cost taxpayers $100 million and take four years to build. The end result of this solution? Four traffic lanes in each direction.

Looking at other options

Many major cities around the world, such as Madrid and Oslo, are trying to reduce car use by banning vehicles from their downtown cores and encouraging residents to use other modes of transportation.

Then there are countries like China, Germany and Denmark which are building bicycle super-highways that range in length from a six-kilometre urban commute to a 100-kilometre journey. Given the dynamics in Edmonton of a spread-out city, a cold climate and an urban plan that was designed with cars top of mind, is it possible to change the “car city” mindset in Edmonton?

And do we want to?

Walking

Back in 1905, the handful of cars in Edmonton was greatly outnumbered by horse-drawn vehicles, and the roads were rutted and tough to navigate. Getting around by foot was a primary mode of transit.

For some people it still is.

The 2016 Municipal Census found that almost 12,000 people cite walking as their primary mode of transportation from home to work.

For many, it’s a low-cost alternative compared to other modes of transportation. But the walkers account for less than four per cent of those surveyed in the municipal census, compared to the 72 per cent who rely on vehicles.

Cycling

Commuter cycling is surging in popularity. Results of the 2015 Edmonton and Region Household Travel Survey show that of all the methods of getting around — including walking, private vehicles and public transport — cycling has experienced the greatest growth, increasing by 4.5 times since 1994.

Data counts on parts of the new downtown bike network tell a similar story, city officials say.

The bike lane on 100th Avenue west of 106th Street saw 847 cyclists on May 18, 2018 — a huge increase over the 196 counted at the same location one year earlier.

The city is continuing to grow the cycling network, with plans to expand it south of the river.

So, is it a matter of build it and they will come?

Melissa Bruntlett, an author and co-creator of the urban mobility consultancy Modacity, believes the answer is yes.

In September, Bruntlett spoke to an Edmonton audience about Vancouver’s experience of building a cycling city.

“There is still backlash, we experience a lot of pushback, but for the most part, we’ve seen numbers increase and see the different types of people using bikes,” she said.

In researching her book Building the Cycling City, Bruntlett learned that ridership naturally increases when a city creates road designs to incorporate cycling.

She says citizens need to begin recognizing that bikes lanes are meant for everyday people. “This is just about a safe space for everyone.”

Safety is the goal of Edmonton’s Paths for People. The volunteer-led group is pushing for a more walkable and bikeable city by supporting infrastructure like a bike network or 30 km/h speed zones.

Public transit

LRT is the future when it comes to mass transit, according to city officials.

City council is investing heavily in LRT, with the newest extension — the Valley Line from Mill Woods to downtown — set to open in 2020.

At the same time, the city’s bus network is being completely revamped. The Reboot Your Route bus network redesign will allow buses, in theory, to move passengers through the city more efficiently by picking passengers up along predominantly major roadways.

This means there will be fewer routes but they will be better connected with LRT lines throughout the city.

LRT. Photo by Kurt Bauschardt

Kalen Anderson is Edmonton’s planning director, whose work includes the combined Municipal Development and Transportation Master plans.

She says Edmonton is not unique among North American cities looking for ways to turn predominantly car-focused roads into ones that encourage active transportation.

“We’ve long had a desire as a city to shift transportation modes away from cars to other modes,” she says.

“But you can’t simply shift without having viable alternatives to use.”

What will make Edmonton stand out, she says, is how residents want to get around their city in the long-term.

“Our future is not preordained,” she says.

“Ultimately I don’t think it should be about trying to convert people from one mode to another. I think it should be about choice.”

So, does Edmonton have a chance to discard its “car city”?

Although she doesn’t live in Edmonton, Bruntlett is hopeful, noting that education about transportation options is key and that ultimately, people will choose what works best for them.

“We’re all just people trying to get around.”

Header photo by Kurt Bauschardt.

Written by:

Edited by:

Tagged: