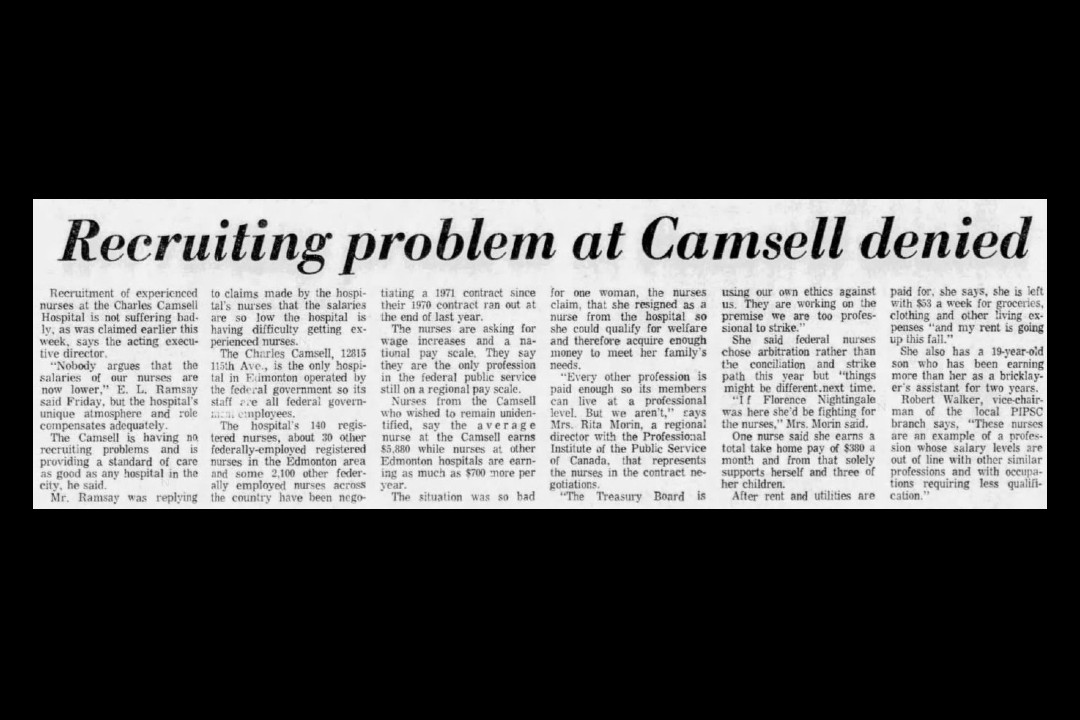

On this day in 1971, officials at the Charles Camsell Hospital were denying news reports that the institution was struggling to recruit new medical staff.

For many, the Charles Camsell Hospital is known as an abandoned, decaying structure that has stood unused in Inglewood for nearly 30 years. But the Camsell, as it's colloquially known, is a building with a long, dark history because of its role in the mistreatment of Indigenous patients.

Before it became a hospital in 1945, the building was a boarding school. Francis Xavier Academy, a Jesuit college, was opened in 1914. The college ran until the 1930s before shutting down for financial reasons. In the 1940s, the Canadian military bought the land and buildings. It then leased them to the United States during the Second World War, which expanded the site and used it to house military members living in Edmonton to help with the construction of the Alaska Highway.

In 1944, as the war still raged in Europe and Asia, the site was converted into a veteran's hospital. In 1945, it was then handed over to the federal government's new Indian Health Services to serve as a site to house patients with tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis rates in Canada are today extremely low, and the illness is treated with antibiotics. In the early 1900s, however, tuberculosis outbreaks were a serious concern. Infections could spread quickly through communities and lead to many deaths. Patients were often isolated in tuberculosis sanatoriums to let the disease run its course without the person infected spreading it to others. The newly-named Charles Camsell Hospital became the largest of these sanatoriums with more than 510 beds. Canadian officials took First Nations and Inuit patients with tuberculosis from all over Western Canada and what is today the Northwest Territories and Nunavut to the Camsell, often without a patient's consent or information given to their families about where they were being taken.

Many spent years at the Camsell. There are accounts of Indigenous patients being pushed to stay at the hospital longer still to receive "citizenship training" as part of the Canadian project of assimilating Indigenous peoples. There are also accounts of abuse and prejudice in the system, as well as chronic underfunding and substandard care compared to what was given to non-Indigenous patients at other facilities.

Some patients never returned home from the Camsell, either because they died or because indifferent officials kept poor records. Patients, including children, were often sent back to different communities than where they were taken from. A cairn in a St. Albert cemetery carries the names of some of those who died at the Camsell.

The design of the hospital itself was also a problem. Since many of the buildings were originally dorms, first for the college and then for the military, they weren't designed for their eventual use. In 1967, the old facility was torn down and a new, purpose-built hospital was erected in its place. Tuberculosis rates declined throughout the 1960s and '70s. The Camsell was eventually classified as a general-purpose hospital, and then transferred to provincial control. It continued to operate until 1996.

There is an ongoing, oft-delayed project to redevelop the hospital lands into housing. In 2021, people searched the site for potential unmarked graves, following similar discoveries at residential school sites across Canada.

Since the hospital's closure, there have been efforts to document its complicated history. A documentary, as well as symposiums and history projects, have gathered stories and experiences of those who were treated at the Camsell. Work continues to uncover the site's past, as well as to tell the larger story of the medical segregation of Indigenous peoples in Canada. It's a story that isn't confined to the past. A recent study headed by a University of Alberta researcher found that First Nations patients leave emergency rooms in Alberta without treatment at a higher rate than do non-First Nations patients.

This clipping was found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist @revRecluse of @VintageEdmonton.