On this day in 1935, tensions were rising between Edmonton's mayor and the province over food relief during the Great Depression.

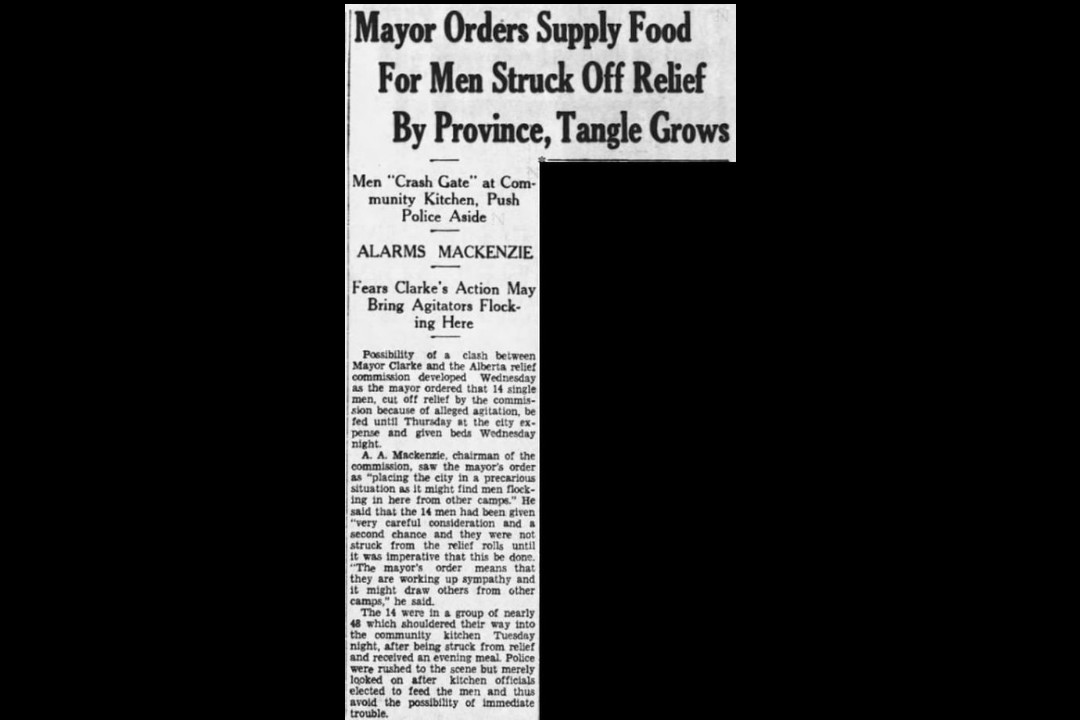

The dispute concerned 14 single men who had been cut off from the province's aid program due to "alleged agitation." In response, then-mayor Joseph Clarke stepped in, demanding that the men be fed and housed for the next few days on the city's dime.

This didn't go over well with the chairman of the relief commission, who said it would lead to more single, unemployed men swamping Edmonton.

Officials may have been wary of an influx of needy men because of memories of 1932, when thousands of farmers, industrial workers, and others gathered in Edmonton to demand more relief from the provincial government. The Hunger March, as it was called, began in the city's market square (where Churchill Square now is), with the intent of marching down to the legislature, despite being denied a parade permit by the city. The marchers set out anyway, soon finding themselves in a fierce fight with police armed with truncheons and mounted on horseback. Eventually, representatives of the marchers were able to meet with Premier John Brownlee, who dismissed their demands. Plans for a second strike were crushed when police raided the headquarters of the organizers a few days later. Dozens of the demonstrators were arrested and tried.

It might be odd that the emphasis was on single men, but at the time, that was an important distinction. During the Depression, every level of government invested in make-work projects and relief programs in the face of devastating unemployment. But the need far outweighed the investment — by 1933, an estimated 25% of Edmonton's working population was unemployed, with about 13% on some sort of relief. What resources were available were largely reserved for married men, who were seen as the primary breadwinners for their families. In 1929, the city commission said Edmonton's emergency relief programs were "for unemployed married men who are bona fide residents," adding that "the city is not in a position to consider others."

For those without families, the message was clear: Leave the city. Some left to scratch out subsistence farms outside of the city limits. For others, their best hope was the remote work camps set up by the federal government, which offered room, board, and a meagre wage. Alberta was the site of three major camps, including ones in Elk Island and Jasper national parks. Since Edmonton was a major rail hub at the time, many of the men travelling to the camps would pass through the city, often riding on the tops of trains when they couldn't pay the fare.

Some of those who chose to stay in the city found shelter wherever they could, including among the trash heaps at the Grierson Dump. The small shanty town eventually grew to about 60 residents, many of them unmarried men who were unwilling or unable to take work placements on farms and work camps. City officials were constantly concerned about the public health risks surrounding the settlement, which saw a couple of outbreaks of typhoid fever. The residents were eventually evicted, and the houses were bulldozed.

The Great Depression might be history at this point, but hunger in Edmonton remains a pressing concern. In 1981, Edmonton's Food Bank opened as the first food bank in the country. In recent years, the problem has grown, with the Food Bank seeing increased demand and not enough donations to keep up. The organization announced that it recently hit its monetary fundraising goal for its holiday campaign, but fell about 20% short of its goal for food donations.

This clipping was found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist Rev Recluse of Vintage Edmonton.