The Alberta government's work to lure data centres to the province and spur artificial intelligence could be a costly effort that exceeds the capacity of our electrical grid and highlight how expensive our electricity is, says the operator of several independent data centres in Edmonton.

"We have something like five or 10% of the expected data centre capacity we'll need for the next five or 10 years," Dale Corse, the CEO of Wolfpaw Data Centres, told Taproot about the Edmonton region. "Could we handle an AI boom? No, absolutely not."

Data centres routinely make news in Edmonton nowadays, yet people rarely get to understand what they are, how they work, and what their business model is. Taproot set out to discover these details from Corse at Wolfpaw, which is one of at least six operators of commercial data centres in Edmonton. Wolfpaw has been in operation since 1998, and has spaces at Rice Howard Place and within two Rogers facilities in town.

The provincial government's goal is to build the data centre capacity that an AI boom would need in Alberta. Its Artificial Intelligence Data Centres Strategy, rolled out in December, sets to develop Alberta's electrical capacity, solve cooling challenges for data centres, and ultimately drive economic growth by seeing companies invest to build centres and AI to use them. The strategy lists objectives for each of these goals, and a map of actions that includes modernizing regulations and collaborating with municipalities. When announced, Minister of Technology and Innovation Nate Glubish said he wants to see $100 billion invested in data centre infrastructure in Alberta over the next five years.

What's a data centre?

"A data centre is a place where you would rent space — either physical space or possibly computer space — to put your IT stuff so that it stays online all the time," Corse said.

Data centres house the computers needed to power the internet, the applications and storage that companies rely on, and increasingly, the computing power needed to create services that use AI.

Corse said the two key functions of a data centre are to keep the electricity on, even during a power outage, and to keep the computers cool. "A data centre would be expected to be able to deal with all of those problems for you so that as a company, you can just concentrate on your business and don't have to also be an IT company on top of trying to do your day to day," he said.

Wolfpaw's facility at Rice Howard Place consumes 5,000 square feet and can draw up to 400 kilowatts of electricity at a time. The company has redundancies, including generators, for its power and cooling to ensure its operations never go down, Corse said. Right now, the centre draws around 200 kilowatts for its clients. By contrast, Corse estimated the average household draws a maximum of 10 kilowatts at any given time.

How does the business work?

A data centre's biggest expense is electricity, Corse said. Real estate is "one of the smaller numbers on the balance sheet," he added. The input cost of electricity is the greatest hurdle, he said, and even building the infrastructure to supply it is pricey.

It costs between $8 million and $10 million to build one megawatt, or 1,000 kilowatts, of data centre power, Corse said. "Some of these AI guys, (they) come to us and they want three megawatts of power. OK, well, that's $30 million worth of equipment just to run it, and then you have the input cost (from electricity) on top of it. So it is a great business, so long as somebody can afford to pay for that. Is it a great business for the small guy? Maybe not."

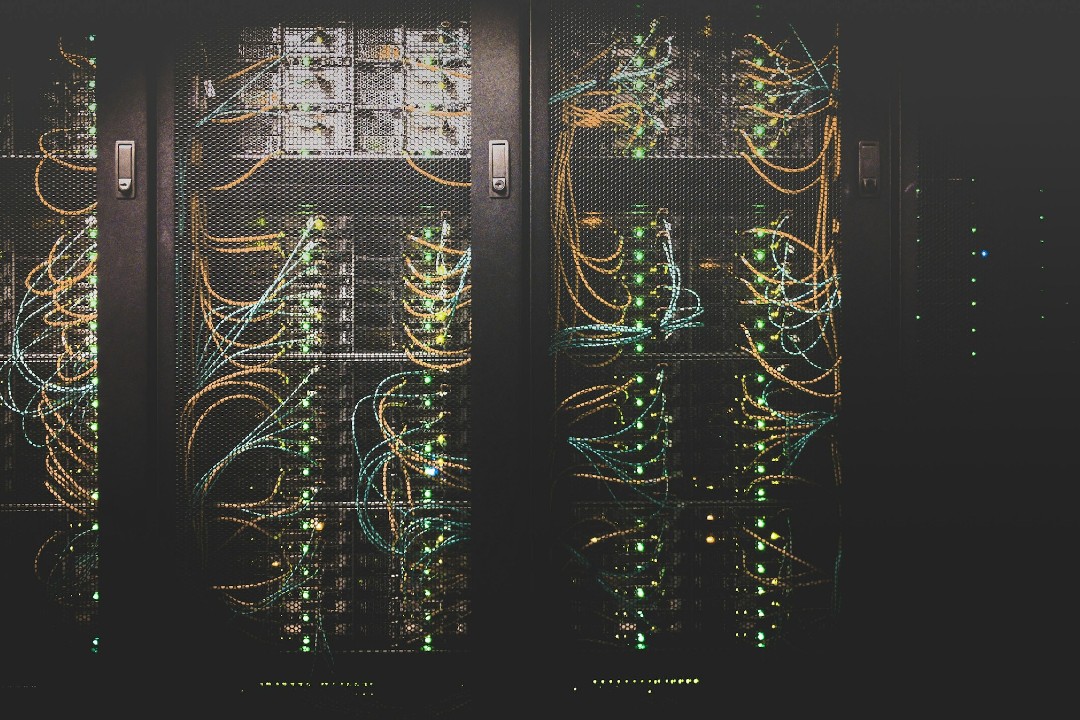

Wolfpaw Data Centres doesn't work at the gargantuan size that artificial intelligence companies require, but CEO Dale Corse knows the industry. He said electricity prices and grid capacity will be integral in the province's push to draw the $100 billion investment that Alberta has targeted. (Taylor Vick/Unsplash)

Who uses data centres?

Wolfpaw employs five people, plus contractors, to serve roughly 100 clients. Corse said naming customers would violate their privacy, but did share that some are based in the United States and that "the vast majority" of non-TELUS-based internet service providers from north and east of Edmonton in Alberta run through his data centres before reaching consumers. Many of Wolfpaw's customers are local, he said, and there are reasons why a client might prefer a data centre to be close by.

"The closer you are to your data, the faster you're going to get it," Corse said. "If you were doing real-time gaming, for example, where the person hits a button on their controller and then something happens at the data centre ... that distance will matter."

Does Alberta have a data-centre advantage?

The province has touted Alberta's colder climate, that it's the only Canadian province with a fully deregulated electricity market, and that it has curbed governmental red tape as the advantages that make it ideal for investors hoping to build data centres.

Corse said Alberta's climate is a benefit, as cooling is the second-greatest challenge after electricity. "Our climate is already cold, so you can use that to your advantage," he said. "It's better than putting (a data centre) into the southern U.S., where it's already hot and then you (need to) cool it off on top of that. It's sort of a natural fit for us here."

But Corse said Alberta's price of electricity and its availability from the grid are less advantageous. Speaking to CBC, he said Edmonton's electricity was the most expensive in Canada in 2023. Energy Hub, which tracks energy in Canada, shows Alberta had the highest average price for electricity among the provinces in 2023, at $0.258 per kilowatt hour. Places where electricity was more expensive in 2023 were the Northwest Territories ($0.41 per kWh) and Nunavut ($0.354 per kWh).

The grid has also been unable to cope with demand, leading to several brownouts.

The province, however, has said new data centre operators will be encouraged to build their own power supply rather than pull power from the grid. During his CBC Edmonton AM interview, Corse said that's like asking truck companies to build highways. He also said the price of electricity needs to be cheaper.

"I don't know how many people are going to have the expertise or the ability to do something like that," he added to Taproot about building power facilities. "If you can't make your own power, then you've got to buy it from the grid. And our power here in Alberta is very expensive compared to the rest of the country, so I think that is something the government, if they're serious about this, has got to work on."

Glubish has proposed natural gas and even geothermal energy be used as power sources for data centres. One example he has highlighted is Wonder Valley Data Centre, an off-grid project using natural gas and geothermal power that's being built by O'Leary Ventures near Grande Prairie. Both Glubish and Premier Danielle Smith provided quotes for the project's press release.

What's happening next for data centres?

O'Leary Ventures is a business started by Kevin O'Leary of Dragons' Den fame. Its plan, to build the world's largest data-centre industrial park, was announced in December. The announcement also said the development will yield more than $70 billion in investment during its operations, which are planned to roll out in phases. The province's major projects webpage lists the cost of Phase 1 of the project at $2.8 billion.

Wonder Valley isn't the only data centre added to the major projects list in December. Beacon, a company with offices in Dublin, Ireland, and Calgary, has proposed five data centres in the province, including ones in Leduc County, Parkland County, and Strathcona County. Each would have 400 megawatts of power available. Only the one located outside High River has been ascribed a cost: $4 billion. The Western Wheel reported that the centre "would include five two-storey buildings on a more than 260-acre parcel and create 300 jobs when operational."

The major projects site notes the facility will contain 400 MW of "onsite power generation capacity," along with two five-storey buildings.

Self-powered data centres are making headlines. California's Edge Cloud Link opened a modular, hydrogen-powered data centre in May, and now plans to open another hydrogen-fuelled facility this summer outside Houston, Texas. Just the first phase of the project is valued at US$450 million, and the data centre should eventually offer one gigawatt (1,000 megawatts) of power.