How to stop discounting pedestrian deaths

A rumination on what Edmontonians can do to make streets safer for those on foot

By Karen Unland, Jeff Cummings, Stephanie Dubois, and Mack Male

The past few months have seen a lot of debate in Edmonton about pedestrian safety, speed limits, bike lanes, Vision Zero, and other issues related to how we can safely get around and get along. One of the many questions this debate raised was this: “Why do we report pedestrian deaths differently from homicides?” Since that was a bit of a rhetorical question, we decided to try a rhetorical answer, an interior dialogue of sorts:

Why do we report pedestrian deaths differently from homicides?

What do you mean?

If a person is killed by another person using a weapon or any other object, it is a big deal, even if the death is ruled an accident, it seems to me. But when a person is killed by another person who is driving a vehicle, it feels like it is less of a big deal. Why is that?

Before we dig into why, we have to figure out whether killing someone with a vehicle is indeed seen as less of a big deal.

OK, so is it?

The media coverage does seem to be different. A pedestrian death will usually warrant a short news story like this one, or maybe a longer one if there is something unusual, such as the deaths of Mary Lynch, 83, and Mariama Sillah, 13, both killed this fall by city bus drivers. But pedestrian deaths are rarely followed through the courts the way homicides are, and media outlets are unlikely to do an annual summary of the victims of cars the way they tend to do with homicides.

That said, the media don’t ignore the issue altogether. For example, Metro Edmonton reported in 2015 on Edmonton’s higher-than-usual number of pedestrian collisions. The city’s police chief was quoted in an Edmonton Journal article on the same issue calling Edmontonians “terrible drivers.”

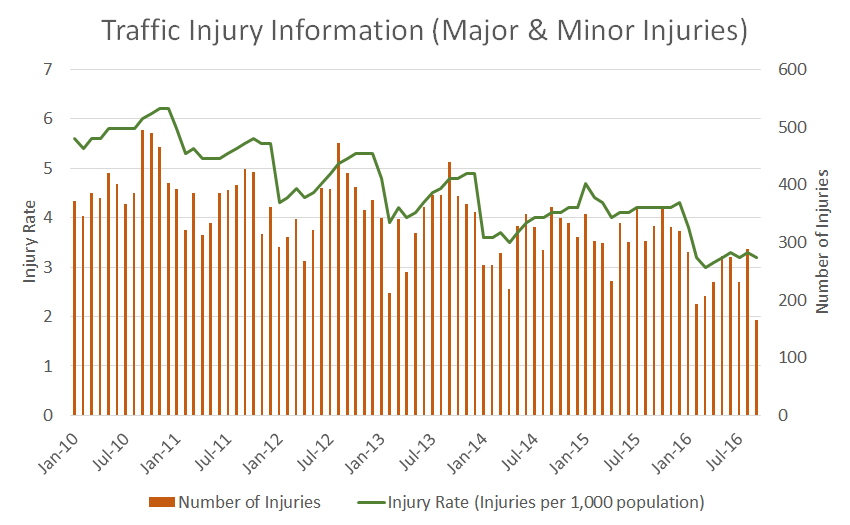

This chart uses data from the City of Edmonton's open data catalogue and shows a gradual decline in the number of injuries per month and in the injury rate (injuries per thousand people). It includes major injuries (the victim was admitted to the hospital) and minor injuries (the victim received medical treatment but was not admitted to the hospital). It does not include fatalities.

You can dig further into the data in the Office of Traffic Safety's 2015 Motor Vehicle Collisions Annual Report in PDF.

Metro Toronto made it its mission this year to pay concerted attention to pedestrian deaths in the wake of a huge number of pedestrian deaths in that city. It is continuing to pay close attention on its Toronto’s Deadly Streets page.

But even Metro acknowledges its focus on this subject is unusual. For the dozens of victims who had died in Toronto since 2015, “death came quietly,” Angela Mullins wrote in June:

Their names went undisclosed, turning them into faceless statistics. There were no flashy news conferences as police celebrated arrests, criminal charges and vowed to clean up “those dangerous streets.” The drivers will likely walk away with fines equal to less than a month’s rent despite being at fault nearly 70 per cent of the time. Calls for meaningful action have been muted if not absent altogether.—Angela Mullins

Why is that the case?

Homicides generally make for a sexier story, says Brian Gorman, an associate communications and journalism professor at MacEwan University.

“With a homicide you have a protagonist and a victim — that’s drama, and drama makes for a good story,” he said.

“For journalists, when it comes to covering pedestrian deaths, the story is a little less interesting.”

Maybe, but there’s still a protagonist and a victim when a driver kills a pedestrian with a car, no?

Sure, but we tend not to blame the driver when we talk about such things. We say “a pedestrian was hit by a car,” not “a driver killed a pedestrian.” As Metro Edmonton’s managing editor Tim Querengesser put it, unless we make a conscious effort, which his news organization is making, we tend to absolve the driver in the language we use to describe such deaths.

Why do we do that?

Part of it is the way the law is written and enforced. In order for a driver to be charged with manslaughter or vehicular homicide, the Crown prosecutor or police “have to prove what they call ‘mens rea,’ which is translated as ‘the intention to do that act,’” explains Edmonton defence lawyer Chady Moustarah.

“It would be extremely hard for a Crown prosecutor, or police for that matter, to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone had intended on killing someone because of the fault of their driving,” he said.

“However, I will qualify this: If the circumstances give rise where the Crown prosecutor or evidence can prove that objectively speaking this behaviour does cause death, then they may arguably have a position for manslaughter.”

Why else?

Part of it is marketing. For example, the concept of jaywalking was invented to counteract the bad publicity that resulted from the carnage in the streets shortly after cars became a common form of transportation. See Adam Ruins Everything — Why Jaywalking is a Crime:

This episode of the 99% Invisible podcast also dives into the manufacturing of the concept of jaywalking. It tends to paint deceased pedestrians as authors of their own misfortune, or at least equally responsible for the bad thing that happened.

You can see the same phenomenon in the rise of the concept of “distracted walking,” which, as this Global News piece points out, is nowhere near as dangerous as distracted driving.

OK, the law and marketing play a role. Anything else?

Well, part of the perception is also related to the fact that the majority of adult Canadians drive. We don’t like to see ourselves as potential killers.

Point taken. Does it even matter whether we treat pedestrian deaths as seriously as homicides?

Dr. Darren Markland certainly thinks so. As an emergency room doctor at the Royal Alexandra Hospital, he regularly puts people back together again, or at least tries, after they’ve been hit by drivers.

Markland suggests if media spent more time and resources covering stories that humanize pedestrians who have been killed or seriously injured — the same types of stories that help people learn about the victims of homicides — Edmontonians would be more aware about the dangers pedestrians and cyclists face every day.

He says the lack of awareness about pedestrians who lost their lives or who have been critically injured has resulted in little influence to get city leaders to overhaul city infrastructure to make it safer.

“We spend a lot of time de-personalizing the victims of pedestrian deaths so that we can cope with not committing to making changes that have to occur on the roads,” said Markland.

“It’s (easier) to maintain the convenience of being able to drive a vehicle in one of the most poorly designed cities in Canada.”

How do we fix that?

Urban planning of city streets has tended to be about moving vehicular traffic efficiently since the invention of the automobile, in Edmonton and many other cities in North America. We expect to be able to drive places quickly. Roads get wider. Walk lights and stop lights become impediments. Speed limits rise. If, as Curbed puts it, “the only real way to make streets safer is to build them that way in the first place,” we have a difficult task ahead of us.

New roads are being designed in a safer way, says Armin Preiksaitis, principal planner at the Edmonton-based design firm ParioPlan.

“It seems to be cars and transit are still taking priority over other modes of transit. But I think there is a shift as I think one size does not fit all.”

You can see that in the proposal by Edmonton traffic engineers to co-ordinate traffic lights on west Jasper Avenue for pedestrians instead of vehicles.

Coun. Andrew Knack sees a shift, too. “I think we have been building our road network with cars in mind. I understand why that might frustrate people and I can also understand the logic that went behind it,” he said. “What we need to recognize is even when you’re designing for a vehicle, you can still design a roadway that moves traffic efficiently and makes it safer for people.”

He emphasizes street design measures such as narrowing the roadways and adding curb extensions are often used in Edmonton to deter speedy drivers.

Even if roads aren’t designed to slow drivers down, you can still lower speed limits, right?

Yes, and that may happen. Knack has introduced a motion to reopen the debate on lowering speed limits on residential roads citywide.

Mayor Don Iveson recently said the upcoming city charters could soon allow the city to set their own speed limits. This would eliminate the need to post expensive signage at every neighbourhood entry point warning of the speed limit change.

A 2010 speed reduction pilot project in six city neighbourhoods cost the city somewhere between $50,000 to $100,000 per neighbourhood just to post signs. But if the neighbourhood speed limit was understood to be at the same rate throughout the city, the signage cost goes down.

It likely won’t be an easy fight. A lot of people remain skeptical that speed kills, for similar reasons to those enumerated above, and they don’t like the enforcement mechanisms such as photo radar.

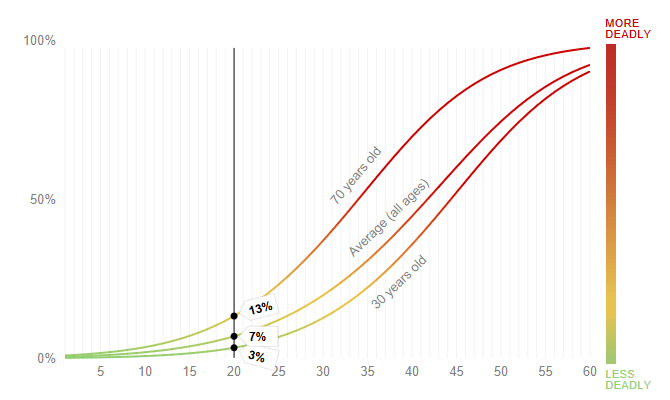

A screen shot from ProPublica's interactive chart from the article Unsafe at Many Speeds, showing the chance of being killed by a car going 20 miles per hour.

Would lowering the speed limit really make that big a difference?

Yes. Check out this interactive chart showing the increase in fatalities with every 10-mile-per-hour increase in speed. The recommended 20 mph would be roughly 35 km/h.

The City of Edmonton is part of the Vision Zero program. Isn’t that supposed to help?

It is. Vision Zero, a strategy modelled after a similar program in Sweden, was approved by city council last year. In Edmonton, Vision Zero is part of the city's road safety strategy until at least 2020, and aims for zero deaths or serious injuries on the road.*

More than 300 people are injured each month because of collisions in Edmonton. There have been 24 traffic fatalities so far this year, 10 of them involving pedestrians. So there’s a lot of work to do.

See also: a Google Map of pedestrian deaths in Edmonton in 2016.

In order to reach the Vision Zero goal, awareness campaigns are underway to change behaviours among drivers, cyclists and pedestrians, said Gerry Shimko, the head of Edmonton’s traffic and safety department.

“We have been advocating for a more traffic safety culture,” said Shimko. “From the Vision Zero perspective, one major injury is one too many.”

The city’s messaging around Vision Zero, including a campaign encouraging people to wear reflective clothing, has come under fire, however, for putting the same onus on drivers, cyclists and pedestrians when only one of those three has the power to kill.

How do we fix that?

Some of it is communication, but some of it is really an empathy problem. It’s like motorists, pedestrians and cyclists are moving around in the same spaces, but in different worlds.

Glenn Kubish sees that on his daily ride to and from work downtown. On every ride, he is accompanied by a tiny video camera that sits on the handlebars of his bicycle, gathering evidence for a running series of drivers behaving thoughtlessly, which he posts on his blog and on his YouTube channel.

“Every trip I make there is something remarkable that happens — something that either happens to me directly, happens to cyclists indirectly, or something that I see happening to pedestrians,” he says.

Being inside a car seems to make it hard for a driver to empathize with those using slower and more vulnerable forms of transportation.

“There is not a sympathy (among drivers) for the way other people move,” said Kubish. “I think drivers have to ride bikes, they have to walk, they have to remember what that’s like when they’re behind the wheel.”

So if our perception changed, our streets might be safer?

Yes. And one of the ways to change our perception is to change the way we report pedestrian deaths. It would be a start, as Streetsblog notes and Metro Edmonton's Querengesser is prepared to do, to avoid these four sins:

- Blaming the victim;

- Failure to consider street conditions;

- Talking about cars, not drivers;

- Calling pedestrian fatalities "accidents," not crashes.

That’s advice for reporters. What about a regular citizen?

Reporters commit these “sins” because they are also citizens who have been socialized to think this way about pedestrian deaths. So we can all work to correct our own tendencies to treat pedestrian deaths as accidental and unavoidable occurrences that are as much the fault of the victim as the driver.

How do you change an entire society’s perception?

It’s happened before. Look at how a concerted effort changed the way we see impaired driving.

Driving after having a few drinks was kind of a normal thing before Mothers Against Drunk Driving and similar organizations started raising a fuss about all of the preventable deaths it was causing in 1980. Now it is common for police to note in news releases whether alcohol is suspected to be a factor, and that is reflected in the reporting, too. Journalists were "sensitized" to the issue of impaired driving by "the publicity-oriented activities of organized groups," writes Charles K. Atkin in Mass Communication Effects on Drinking and Driving.

So what can we do to bring about a similar change to prevent pedestrian deaths?

Here are some places to start:

- Understand you’re wielding a deadly instrument when you drive a car. Accept that a few minutes added onto your journey are worth the reduced risk of killing someone or leaving them with a catastrophic injury if you make a mistake.

- Make your voice heard when the public is consulted. For example, you can weigh in on the pedestrian-centred traffic lights on Jasper Avenue. Joining the Edmonton Insight Community would give you more chances to speak up.

- Make sure city council knows where you stand as it begins the debate on speed limits. And remember — next year is an election year.

Header photo courtesy of Mack Male. Speed chart courtesy of ProPublica.

*An earlier version of this story said Vision Zero's goal is zero deaths or serious injuries on the road by 2020. In fact, Vision Zero is part of the city's road safety strategy until 2020, but there is no set end date on achieving zero deaths or serious injuries (though sooner is better than later.)

Written by:

Tagged: