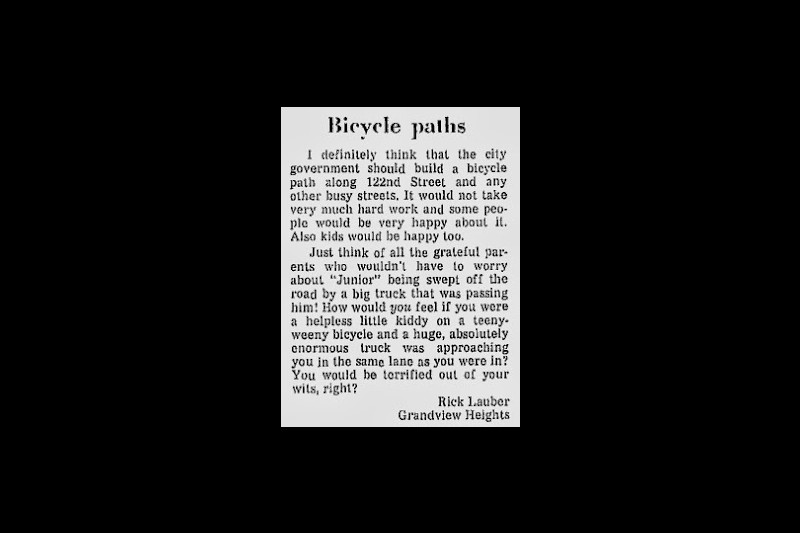

On this day in 1973, one Grandview Heights resident was calling for bike lanes in the city.

In his letter to the Edmonton Journal, Rick Lauber called for a bike lane along 122 Avenue and other busy roads. His concerns were mainly for the safety of kids, asking how readers to imagine how it would feel "if you were a helpless little kiddy on a teensy-weeny bicycle," passed on the road by a truck.

A year later, Edmonton would build its first dedicated bike path, but it wasn't where Lauber hoped it would be. Instead, the trail connected the University of Alberta to Michener Park, a student residence for couples and families. Over the next couple of decades, Edmonton added about 150 km of painted bike lanes on city streets and about a third as many paved paths in the river valley.

In 1992, the municipal government released its Bicycle Transportation Plan, noting that while recreational biking was "extremely popular," the number of people commuting on two wheels was relatively small (both groups were growing, however.) That plan laid out dozens of recommendations for improving and encouraging cycling in the city, including adding many more bike lanes, widening the curbs on roads to give more room to cyclists, and adding more secure bike parking.

The 1990s also saw a movement to repurpose old railway right-of-ways as multi-use trails, led by groups like Bike Edmonton. The push saw some success, most notably the Ribbon of Steel, which in 2003 turned the old rail lines that run south of Jasper Avenue into a walking and cycling path that runs along the streetcar route.

As the number of bike lanes increased, so did the number of people using them, for the most part. In 2015, there was a heated debate over eight kilometres of painted bike lane along 95 Avenue, a mere two years after it was put in. City councillors admitted that poor public consultation was done before the lanes were installed and argued they were underused and unsafe as a result. Eventually, the lines were removed, and the city promised changes to its consultation process.

While the city had hundreds of kilometres of bike lanes, they were little more than paint separating cyclists from cars. Better than nothing, perhaps, but cycling groups argued they remained unsafe. In 2017, Edmonton built its first protected bike lane, making it one of the last major Canadian cities to do so. (Well, unless you count the protected bike lane that some random person made along Saskatchewan Drive with tape and pylons a year previous.)

The protected bike lanes stirred up more than a little bit of controversy, even becoming a minor election issue the following year. But they proved to be a model, leading to new routes in Old Strathcona, central Edmonton, and other areas of the city.

Plans to expand the cycling network in Edmonton have accelerated, although not without some backlash. Last winter, the city removed one of a pair of protected bike lanes from Victoria Promenade after complaints of lost parking. Around the same time, city council approved a $100-million investment to fill in gaps in Edmonton's bike network, a decision that predictably brought on strong reactions from both supporters and detractors.

Those curious about what a cycling city looks like may want to attend Curbing Traffic: An Evening with Chris Bruntlett on Oct. 19, which will explore cycling infrastructure in the Netherlands.

This is based on a clipping found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist @revRecluse — follow @VintageEdmonton for daily ephemera.