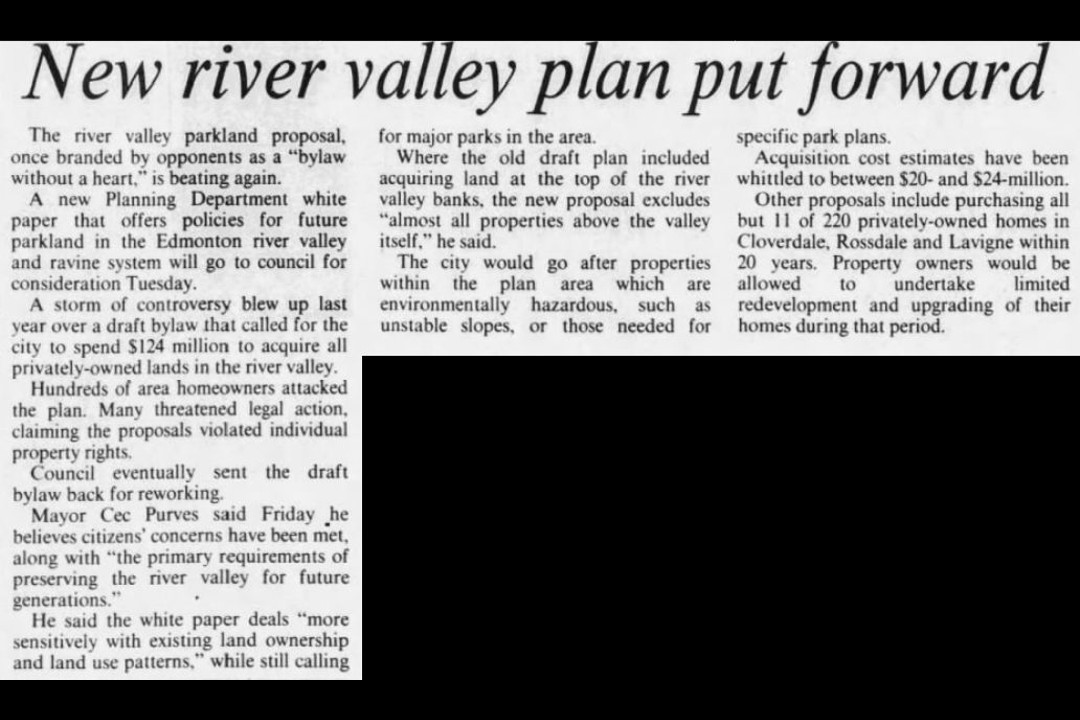

On this day in 1982, Edmonton was debating something called the river valley parkland proposal.

The proposal, which called for major parks to be developed in the valley following a city purchase of land, was itself a response to the controversy that had exploded a year before. That controversy erupted when city officials floated the idea of purchasing all privately owned properties along the river valley. That $124-million dollar idea didn't go over well with many of the people who owned properties within the valley, some of whom branded the idea "the bylaw without a heart," according to the Edmonton Journal. It was a dramatic reaction, but not surprising given Edmonton's unique and sometimes fervid relationship with its river valley.

The river valley we have today is quite different from the one that existed at the beginning of the 1900s. Like most cities at the time, the North Saskatchewan River functioned as the industrial heart of early Edmonton. The banks of the river offered wood for lumber mills, coal for mines, clay for bricks, and even a small gold industry. The river also provided a fast, cheap way to move products and people to and from the city before the rail lines arrived.

But there were people even then who called for the river valley to be preserved as a natural space. In 1907, Frederick Gage Todd created a report for the city about how to provide park space for Edmonton's rapidly growing population. Todd, one of the country's first landscape architects, advocated for much of the valley to be preserved as a park for the public good.

While Todd's influence was important, it was the North Saskatchewan itself that changed the course of development in the valley. The worst flood in the city's history hit in 1915. River water eventually reached 10 metres above its normal level. The flood wiped out more than 700 homes and 50 buildings, washing away much of the industry centred on the river. Understandably, many were reluctant to rebuild what was lost to the water. Following the flood, both the city and provincial governments adopted many of the principles from Todd's preservation proposal. The City of Edmonton acquired more than 100 properties along the river over the following decades. Those, along with more land the city purchased in the decades following the Second World War, created what is now the largest urban park in Canada.

Of course, that didn't mean that the river valley was off limits for development, especially those that catered to drivers. The 1969 Metropolitan Edmonton Transportation Study (METS) plan was one of the most dramatic plans to involve the valley. The massive plan envisioned covering much of the natural areas near the river with freeways. Fierce opposition put the brakes on METS, but only after the construction of the James Macdonald Bridge and accompanying freeway infrastructure in the Cloverdale and Rossdale neighbourhoods. The METS sparked another wave of preservationist sentiment into the 1970s.

In 1985, shortly after the "bylaw without a heart" debate, Edmonton passed the North Saskatchewan River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan, which defined the boundaries of the river valley and created development policies to protect it as both a recreational and natural space. Still, the plan noted that as the city grew, the debate over its relationship with the river valley would, too.

That's still true in 2024. The city is now modernizing that 1985 plan, which will define the future of the river valley. It released a draft of its report this summer, which emphasizes principles such as ecological integrity, access, and Indigenous engagement. The results of the latest round of public consultation on the plan are set to be released this fall.

This clipping was found on Vintage Edmonton, a daily look at Edmonton's history from armchair archivist @revRecluse of @VintageEdmonton.