On a recent evening, Les Skinner stood before students in the program room at the Highlands branch of the Edmonton Public Library. He put his hands over the left side of his chest, using Cree sign language to signal the nêhiyawêwin word for grandma.

Skinner said "nôhkom." The class repeated the word.

Next, Skinner put his hands on the right side of his chest: "nimosôm," he said. Grandpa. The class repeated.

He put one hand on his left side, signing the word for mother: "nikâwiy," he said. He put his right hand on the right side of his chest: "nôhtâwiy." Father.

Skinner teaches a twice-weekly nêhiyawêwin language class at the Highlands library, with one of the classes running online. There are usually about 10 to 15 students in person and 30 for the online classes. Some of the students are Indigenous, others are from settler backgrounds. There are teenagers and seniors, dads and young women.

According to the 2021 census, 5.8% of Edmonton's population is Indigenous, but less than 1% of Edmontonians speak an Indigenous language. About 1,500 people said their first language is Cree, and 335 people said Cree is the language they speak most often at home.

The library created the language-learning class about seven years ago in partnership with the Canadian Native Friendship Centre. Its goal is to enhance literacy.

But though it's a language-learning class, Skinner teaches literacy that goes beyond vocabulary, pronunciation, and verb tenses. "We try to have a built community, and we try to build a little bit of kinship at the same time as we're learning the language," he said.

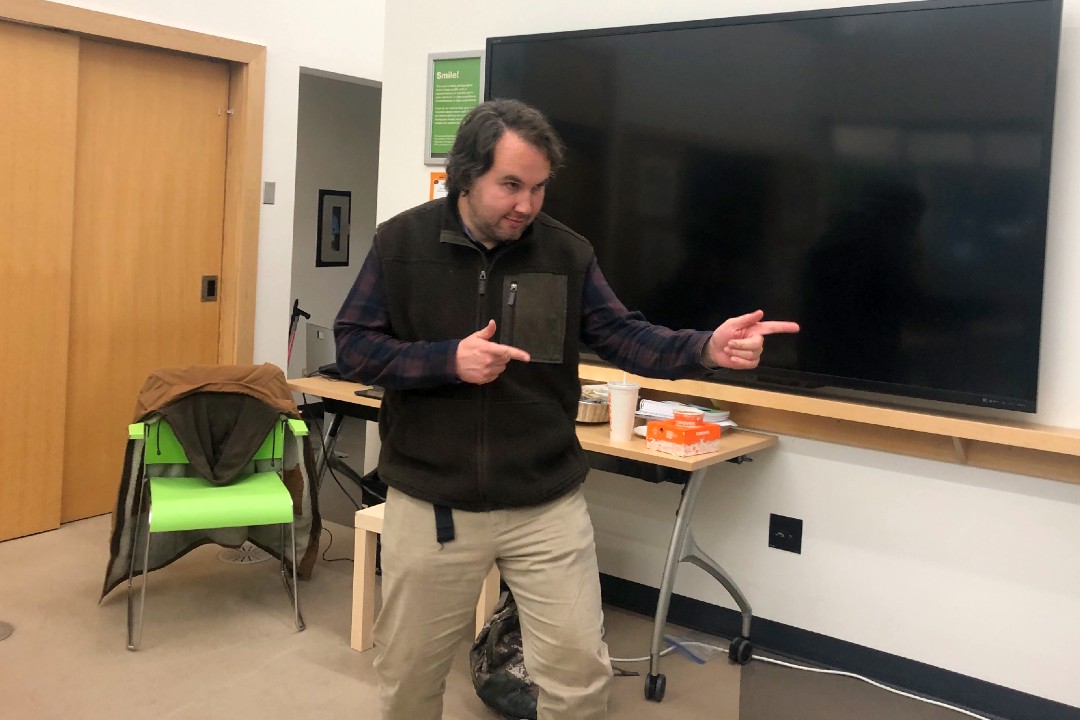

Les Skinner signs the action for killing a moose while he tells a story during a nêhiyawêwin class at the Edmonton Public Library. (Stephanie Swensrude)

Food central to learning

Skinner, who is Métis, started the class by telling stories. He explained the impact that residential schools have had on Cree and Métis people ahead of a short documentary, Man Who Chooses The Bush, which he said shows that impact.

But Skinner stopped the video just seconds into it. "Wait, what is that?" he said, pointing at an aluminum-covered baking dish. "Are we going to eat that?"

Food is one aspect of the class that isn't directly connected to language but is important, Skinner later said. On this evening, a student had brought a Métis bread pudding, though sometimes Skinner brings moose stew, or others bring bannock. "We learn a little bit through sharing food … that adds to the community aspect to it," he said.

Tom Radford's Man Who Chooses The Bush, a National Film Board documentary released in 1975, tells the story of Frank Ladouceur, a Métis man who lives in northern Alberta, traps and skins animals, and plays the fiddle.

"In that video we watched, that man was educated," Skinner said. "He's a bushman with all these learning skills that are developed. And when they put us into residential schools, they took us away from getting those traditional learning skills."

After the documentary, Skinner returned to Cree kinship terms, or words to refer to relatives. He said there is no nêhiyawêwin word for aunt or uncle — you call your aunt nikâwiy (mother) and your uncle nôhtâwiy (father) because in Cree culture aunts and uncles have the same responsibility, authority, and love for their nieces and nephews.

Your mom and dad's siblings are like additional parents. You call your cousins nîtisân, the same word for siblings because they are the children of your nikâwiy or nôhtâwiy. The siblings of your grandma and grandpa are also nôhkom (grandma) and nimosôm (grandpa).

When Skinner gets his students to repeat those words, he's not just teaching vocabulary, but also the structure that Cree society had before colonization.

"We're trying to learn our way of life at the same time, but we're stuck here in that we're learning it mostly through stories," Skinner said.

Students absorb culture

Student Gregory Bird said he grew up with his mother's nêhiyawêwin books from university in his house.

"I started reading through them and I learned the whole way how to write the syllabics, but it's not the speaking part," Bird said. "That's why I came here, to hopefully speak it."

This was Bird's first class, and he came because he wanted to teach nêhiyawêwin to his family one day.

"One of my grandmas (speaks Cree) but I never get to see her because she lives far away," Bird said. "One day I hope I'll be able to teach it, speak it fluently with everybody I know."

Fellow student Jana Maresova usually attends the classes online from her home in Jasper but on this evening stopped by in person while she was in town.

"It's a sign of respect to the place where I live and to the people that lived here originally," Maresova said of her decision to take the classes.

She added learning Cree helps her connect with her Cree friends. "Everybody should learn Cree … it's very cool to just learn something new, completely different than what you're used to."

Need to practice spurs class

Skinner started teaching nêhiyawêwin 12 years ago.

"I started teaching Cree as a way of learning because I was learning at a certain point, I wanted to have more people together who we could learn by in practice, and I didn't have enough people that were at my level," he said. "So I thought, 'Well, I'm going to teach people to get them to my level.'"

Skinner didn't grow up speaking the language, but he counts himself lucky to have grown up with it in his life.

"I used to stay with my grandparents lots when I was a little kid, and my grandma's mom used to talk mostly Cree, really strong Cree," he said. "And she used to make me (do the) Red River Jig. From that, I can't remember how to talk Cree, but what I can remember is how it felt, how she loved me, and that's how come I always want to talk Cree … there's lots of young people that grew up that never heard that, never had that experience. Lots of families were more broke, and I think I was lucky that I had that experience as a kid, actually."

Skinner said non-Indigenous students are welcome in the classes, but the priority is to teach Indigenous people.

"Cree class should always be one of the few places where a native can come to and they feel like it's their time, they're the ones that are in the spotlight," Skinner said. "This is where they belong and this is their home."

The weekend that followed the class saw Skinner hold his annual holiday party, where he invited students to the Ukrainian Centre. There's going to be fiddling and moose stew, and he's teaching a Métis jig step.

Skinner said the real learning of the Cree way of life needs to take place outside the classroom.

"Through stories, I try to make my students have that desire to go out and be out on the land," he said. "It's on the land that we were able to have extended families live together and practice the culture. We want it to be a living thing. We don't want it to be our heritage, it's what we are right now. And we want to be able to live it right now. There's still a lot of barriers in modern society to being able to do that."