Cree language classes go beyond words

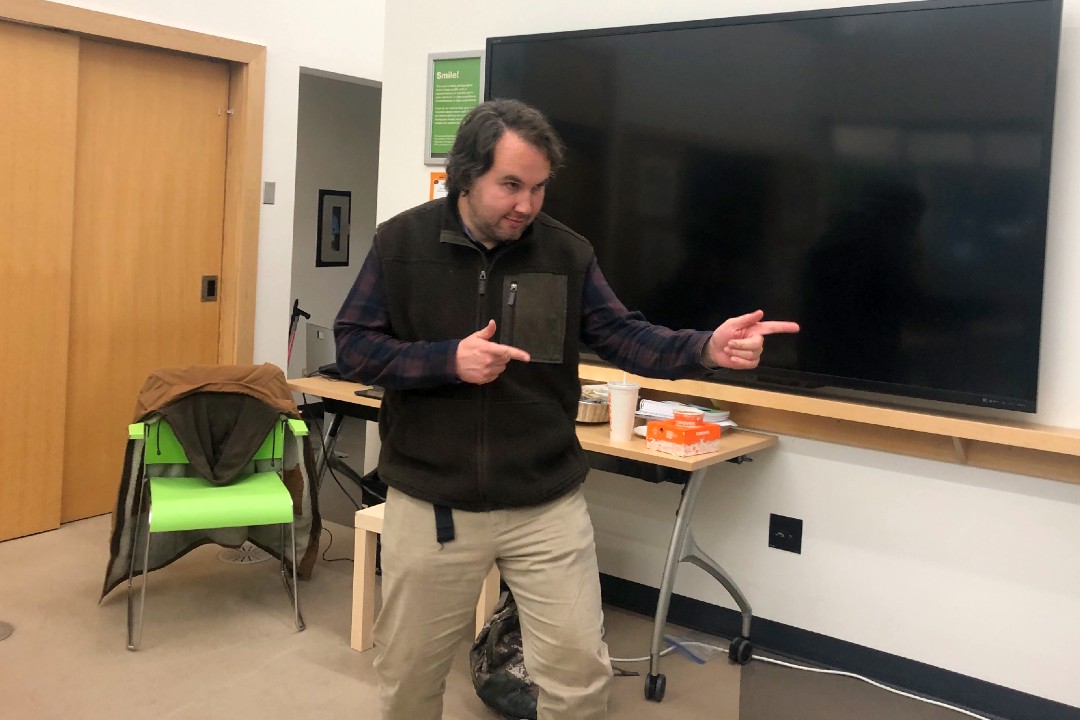

On a recent evening, Les Skinner stood before students in the program room at the Highlands branch of the Edmonton Public Library. He put his hands over the left side of his chest, using Cree sign language to signal the nêhiyawêwin word for grandma.

Skinner said "nôhkom." The class repeated the word.

Next, Skinner put his hands on the right side of his chest: "nimosôm," he said. Grandpa. The class repeated.

He put one hand on his left side, signing the word for mother: "nikâwiy," he said. He put his right hand on the right side of his chest: "nôhtâwiy." Father.

Skinner teaches a twice-weekly nêhiyawêwin language class at the Highlands library, with one of the classes running online. There are usually about 10 to 15 students in person and 30 for the online classes. Some of the students are Indigenous, others are from settler backgrounds. There are teenagers and seniors, dads and young women.

According to the 2021 census, 5.8% of Edmonton's population is Indigenous, but less than 1% of Edmontonians speak an Indigenous language. About 1,500 people said their first language is Cree, and 335 people said Cree is the language they speak most often at home.

The library created the language-learning class about seven years ago in partnership with the Canadian Native Friendship Centre. Its goal is to enhance literacy.

But though it's a language-learning class, Skinner teaches literacy that goes beyond vocabulary, pronunciation, and verb tenses. "We try to have a built community, and we try to build a little bit of kinship at the same time as we're learning the language," he said.