Edmonton is expanding the story it tells about itself by adding a community archivist, who is tasked with actively addressing blind spots in the city's work to preserve information by seeking new archives to add.

"I think there's been this myth of archival neutrality when really archives are political bodies," Jia Jia Yong, the first community archivist at the City of Edmonton Archives, told Taproot. "Archives are very much geared to benefit certain people, and also geared to be a barrier to other people."

The archives' main purpose for the city is to house all of its records within the Prince of Wales Armouries Heritage Centre at 10440 108 Avenue NW. In tandem, archivists work to preserve stories about all manner of Edmontonians. They house documents, photos, videos, and more. The city deposits its own records; citizen stories, however, are obtained primarily through donations.

While Yong performs typical archivist duties like cataloguing incoming materials and assisting researchers to navigate the collection, what sets her role apart is her outreach. She forges relationships with potential record donors through cold calls, attending events, holding meetings, and designing promotional materials.

"We definitely hope to work with cultural communities and communities of interest across Edmonton … for all communities to be included," Yong said. "Very often, the conversations I have with people are simply just introducing what archives are, and to some extent affirming that their history and their story and their materials and their records are of value."

She's seen the fruits of her outreach labour. Jim Yee, whom she met at an event, decided to donate his family records and even joined Yong in the archival process. Similarly, the Edmonton Japanese Community Association donated records, leading to a pleasant surprise.

"In those organizational records there was actually a film reel that nobody knew what was in it. It had just been sitting in their library at their centre for years," Yong recalled. The film turned out to be a documentary made by Alberta's culture ministry in the 1970s that showed the lives of Japanese Edmontonians at the time, including footage of the second-ever Edmonton Heritage Festival in 1977. Yong is planning to screen the film with the community association in the hopes of drawing further interest in the city archives.

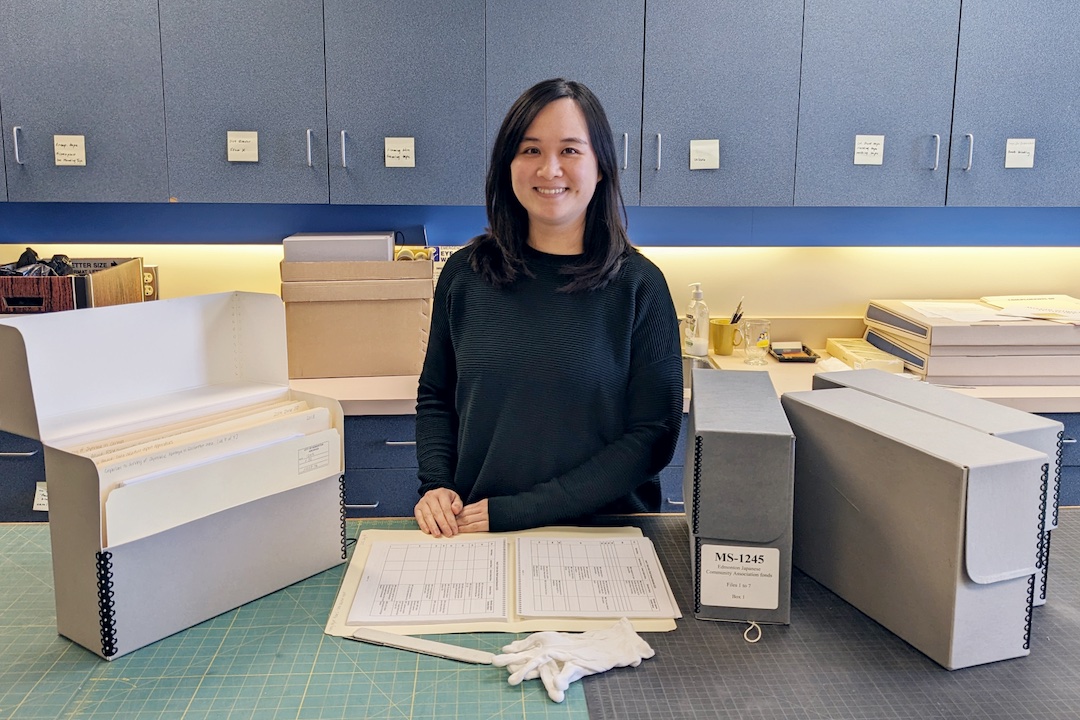

Jia Jia Yong is the first community archivist at the City of Edmonton Archives. Much of her job is to go out into the world to attract records, rather than wait for donations. (Supplied)

It's natural to wonder why community archival work matters. Yong said archives often exclude people with low levels of education, who do not have the time or money to organize and donate records, or who store information through oral tradition.

"I'm trying to think of any policies or procedures within the organization that we can use to address barriers for people to access the archives," Yong said.

Edmonton created the community archivist position in part because queer historian Ron Byers lobbied the city to do so. He wanted records donated by Michael Phair, Alberta's first out, gay politician, to enter the city's official vault.

Yong said those records include thousands of photos and measure 13 kilometres in width. Around 70% of the photos have been at least partially identified, thanks to "identification parties" Byers helped to organize. These entailed a gathering of 2SLGBTQ+ community members who were around at the time the photos were taken, who combed through photos to name places and the people depicted.

Beyond who is included in archival records, use by "researchers" is more diverse than one might think. The City of Edmonton uses the repository for its work and academics come to research things, but even homeowners planning renovations, people curious about their family history, and artists make use of the archives.

"We just call them researchers, but that doesn't mean they have to be academics," Yong said. "Really, anybody can come to the archives … (but) we do request that you make an appointment."

Prior to the Edmonton position, Yong was the archivist for Musée Héritage Museum in St. Albert. She worked by herself at the museum, meaning she was what archivists call a "Lone Arranger." She hopes to the city renews her role at the end of her contract. Even more important, she said, is that a community lens exists with or without her.

"I really hope that this work exists for the long term, and isn't just a kind of token equity, diversity, inclusion project that lasts for four years and looks good and then ends," she said. "I'm really hoping to make a lasting impact."

Yong is currently working with 2SLGBTQ+, Chinese, Thai, South Asian, and Japanese communities, among others. She's also begun early conversations with Edmonton's Black communities.

The city's archives webpage has instructions on how to plan a visit and how to donate records.