Drink pouches are ubiquitous but hard to recycle, a problem that a new three-year research project by the Alberta Beverage Container Recycling Corporation at NAIT's Applied Research department is working to solve.

"The drink pouches are problematic due to the multiple layers, but they are recyclable," Guy West, president and CEO of the recycling corporation, told Taproot. "Ideally, we would like (a) higher quality of recycling if we can. But right now, nobody has that solution, so that's why we've partnered with NAIT."

The recycling corporation is responsible for collecting and recycling all beverage containers that bottle depots receive in Alberta. That includes drink pouches (think Capri Sun, Kool-Aid Jammers, or Fruit-tella pouches), which, unlike most other beverage containers, lack a consistent form or construction. This makes them difficult to recycle to their greatest potential because they are often made of layers of materials, including aluminum, plastic, and paper.

Currently, Alberta's drink pouches end up in British Columbia, where they're incinerated for byproducts used to supplement natural gas in industrial processes. The aluminum, plastic, and paper in the pouches can meet the higher-quality-of-recycling criteria West mentioned, but only if they are separated.

As NAIT begins the first stage of the $300,000 research project, one expert said chemical options might help separate the materials to allow pouches to meet high-quality criteria for recycling.

"There are a variety of different techniques that can be done," Kelsey Deutsch, an industrial surface chemist who is part of the clean technologies team at NAIT Applied Research, told Taproot. "One of them is using solvents to try and separate the different layers. We would potentially look at mixing the pouches in small pieces and stirring them in solution or solvent at an elevated temperature. Perhaps there's also other techniques, such as pyrolysis, which is heating the pouches and the plastics in an inert atmosphere to try and break down those chemical constituents into smaller building blocks."

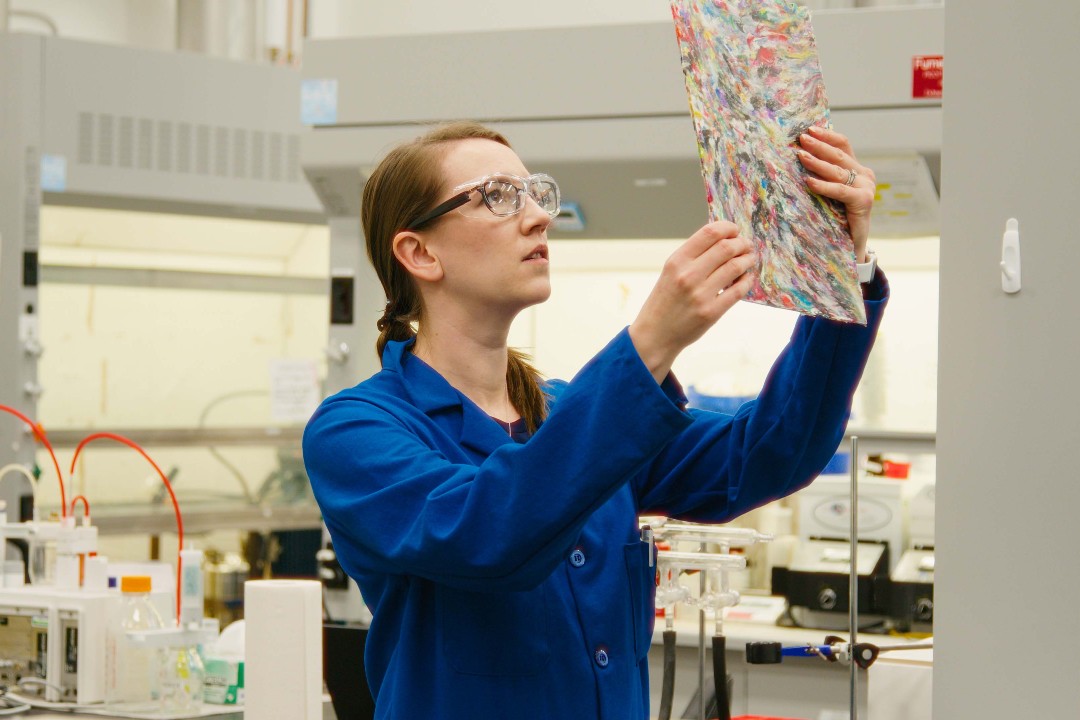

Kelsey Deutsch, an industrial surface chemist who's part of the clean technologies team at NAIT Applied Research, is looking at ways to chemically separate the materials that drink pouches are made of. (NAIT/Sachin Pundir)

One valuable element in beverage pouches to separate is plastic, because of its high recycling potential, West said.

"Plastics recycling in beverage containers works very well," he said. "Eighty-five % of the containers that we receive or we recover (that are plastic) … are processed through to the point where the resulting product meets food-grade standards."

That processing is handled by B.C.-based Merlin Plastics, which the recycling corporation also contracts for drink pouches. West said the company was the first to receive certification in both Canada and the United States to produce food-safe packaging from recycled materials.

NAIT Applied Research has a $10 million Plastics Research in Action initiative, including a project Deutsch led that used plastics to build a plastic sheet prototype to be used as concrete formwork in the construction industry. Deutsch said it's "not beyond the imagination" that plastic and other materials used in drink pouches could be part of NAIT's work in the circular economy.

Another advantage for recycling in Alberta, West said, is that it's the only province where drink packaging must be registered with the Beverage Container Management Board to prove it can be recycled. Packaged beverage manufacturers also pay fees to fund the recycling corporation.

However, West said one weak point is consumer awareness and behaviour. Only 8.5 million of the 14.8 million pouches sold in the province last year were recovered by the depot system.

Alberta Beverage Container Recycling Association president and CEO Guy West said the organization has invested $300,000 for a new project with NAIT Applied Research to find better recycling options for drinks pouches — and potentially find a better way to manufacture the packaging type. (Supplied)

"Part of the problem is that they are not traditional beverage containers," West said, adding that the recycling corporation runs awareness campaigns on drink pouches. "Now, awareness is one thing, but having (someone) take (a pouch) to the bottle depot is another. If they're out in a park, and they've got a partially filled or unfilled package that is not sealed, are they going to take it back home, or are they going to look for another option?"

A silver lining, he said, is that municipal recycling staff in Edmonton (and Calgary) are good at finding refundable containers and taking them to a bottle depot.

West said the makeup of pouches is not uniform. The primary focus of manufacturers, he said, is to meet food safety standards for their various product types. But part of the research at NAIT may yield a formula for a more recyclable pouch that meets those standards, and could potentially entice manufacturers to adopt the new option.

"The more we can learn, the more we can inform, the more we may be able to modify the packaging, or have them modify the package, (the better)," West said. "If we can identify if there's an alternative way in which to do this, and still achieve a viable package without a whole lot more cost, that may be something that they look forward to."

Recycling is not without its critics. Plastic recycling faces a high degree of scrutiny, globally, from critics who say recycling "is failing."