Groups researching how to better recycle the 15 million pouches Albertans consume yearly

Drink pouches are ubiquitous but hard to recycle, a problem that a new three-year research project by the Alberta Beverage Container Recycling Corporation at NAIT's Applied Research department is working to solve.

"The drink pouches are problematic due to the multiple layers, but they are recyclable," Guy West, president and CEO of the recycling corporation, told Taproot. "Ideally, we would like (a) higher quality of recycling if we can. But right now, nobody has that solution, so that's why we've partnered with NAIT."

The recycling corporation is responsible for collecting and recycling all beverage containers that bottle depots receive in Alberta. That includes drink pouches (think Capri Sun, Kool-Aid Jammers, or Fruit-tella pouches), which, unlike most other beverage containers, lack a consistent form or construction. This makes them difficult to recycle to their greatest potential because they are often made of layers of materials, including aluminum, plastic, and paper.

Currently, Alberta's drink pouches end up in British Columbia, where they're incinerated for byproducts used to supplement natural gas in industrial processes. The aluminum, plastic, and paper in the pouches can meet the higher-quality-of-recycling criteria West mentioned, but only if they are separated.

As NAIT begins the first stage of the $300,000 research project, one expert said chemical options might help separate the materials to allow pouches to meet high-quality criteria for recycling.

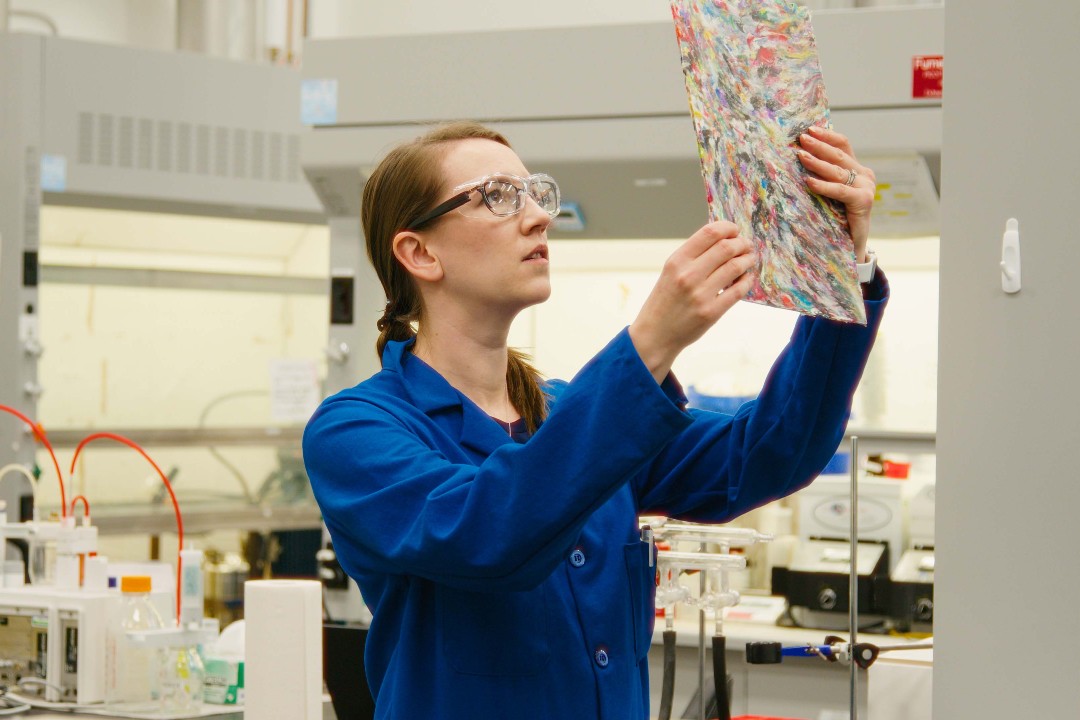

"There are a variety of different techniques that can be done," Kelsey Deutsch, an industrial surface chemist who is part of the clean technologies team at NAIT Applied Research, told Taproot. "One of them is using solvents to try and separate the different layers. We would potentially look at mixing the pouches in small pieces and stirring them in solution or solvent at an elevated temperature. Perhaps there's also other techniques, such as pyrolysis, which is heating the pouches and the plastics in an inert atmosphere to try and break down those chemical constituents into smaller building blocks."