Several election scrutineers who were inside voting stations on Oct. 20 spoke to Taproot about their experiences watching a vote result roll out far slower than many hoped.

They told us the processes Edmonton Elections staff were told to use to count ballots left room for improvement and that the well-reported delays in results could be linked to these processes. Our interviews with scrutineers also found that the counting process was not consistent across stations, that several scrutineers saw ballots for mayor or council rejected due to missing signatures from election staff, and that some elections staff were concerned about their pay based on extra hours worked.

On that point, Edmonton Elections told Taproot in a statement that its standard practice is to pay workers a flat fee for training and election-day work, but it has now changed that for this election due to the delays. Workers will receive the original flat fee plus additional pay, Jennifer Renner with the organization said. "We understand that many election workers went above and beyond to ensure that voting and counting procedures were implemented," Renner said.

View from inside

Scrutineers are volunteers linked to one or several campaign teams who stand in the room and scrutinize the elections staff working with ballots. They push for a ballot to be rejected (or a rejected one to be counted) if they feel something is amiss, watch staff seal and unseal ballot boxes, and relay information to their campaign teams far ahead of official results filtering out to the voting public.

"We're just watching to make sure that the counts all add up at the end of the day," Karl Parkinson, who scrutineered for the Andrew Knack campaign at Allendale School, told Taproot. "Basically, it's just sort of a check to make sure that nothing sort of funny happens."

The organization's budget was increased by $4.8 million as compared to the 2021 municipal election, with $2.6 million alone being attributed to the hand-count, requiring 1,230 election-day workers. That increase was to account for the increased human effort required to hand-count the entire vote in 2025, as required by the United Conservative Party government's Bill 20, which outlawed the use of voter tabulator machines — machines that have been in use in Edmonton municipal counts since the 1960s. Calgary, which budgeted an additional budget of $3.3 million for its work, released results at a far faster pace than did Edmonton.

Count challenges in Edmonton saw some call for a full election audit. The vote in Ward sipiwiyiniwak was recounted and Thu Parmar won, after unofficial counts had suggested Darrell Friesen had won.

To understand what was happening, Taproot spoke with scrutineers who watched it up close. Here's what they said.

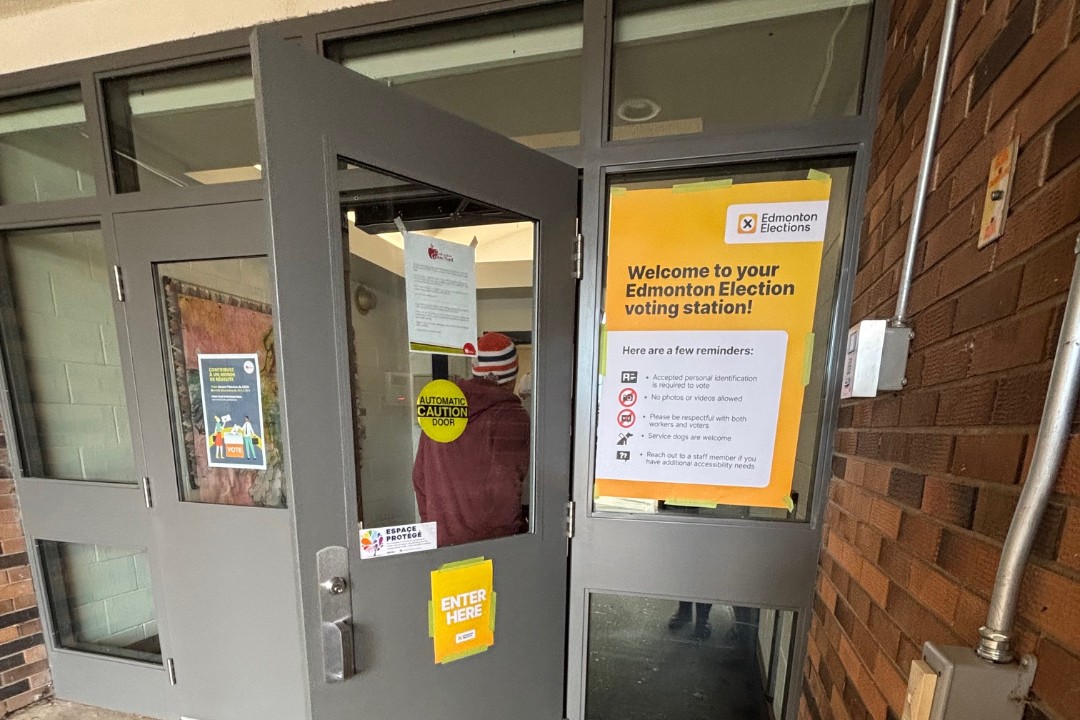

A person walks to a voting station on Oct. 20, 2025. (Tim Querengesser)

Karl Parkinson

- Scrutineer for: Andrew Knack

- Where: Allendale School

- Arrived: 7:30pm

- Left: 12am

"The slowest part, I think, was they had to sort every single ballot," Parkinson said.

Parkinson said he watched the mayoral count, where there was one table and four counters. When it came to the count, "they just split up the big pile of ballots into four of them, and then each person had several names in front of them," he said. The four would look at the ballot and say, "'OK, is it for one of the names in front of me?'" he said. "If it was, they would put it there in a pile; otherwise, they would pass it to the right."

This resulted, as Parkinson highlighted, in ballots being sorted multiple times before being counted, taking extra time and staff attention to move around the counting table to their designated counter. And it created further difficulty. Of the roughly 1,250 votes cast for mayor at Allendale, Parkinson said nearly 700 of them were for Andrew Knack. "Over 50% of them were all in one big pile, so it was a little inefficient," he said. "One person was having to manage all the Andrew Knack ballots, and the other people maybe had 100 votes for Michael Walters, or a couple hundred for Tim Cartmell."

Parkinson said there were four people counting mayoral votes at one table at Allendale, four people simultaneously counting council votes at another, and three counting public school trustee votes at yet another (the Catholic school trustee was acclaimed). He said the mayoral count ultimately ended up being counted four times: The first two counts did not match, the third count got a different number from the first two, and the fourth matched the third.

"I don't know what training the ballot counters got, but other than putting the names out and doing the around-the-table sorting thing, there didn't seem to be an official way to count the ballots," Parkinson said. He added that at least two counters had worked during the election, too, so they had been there since 8am, adding an element of fatigue. Had the counters been trained to make piles of 10 ballots, or 50, and offered some simple counting guidelines, "that probably would have helped," he said. He further added that having more experienced people in leadership positions could have aided the process.

Scrutineers who watched the counting process at voting stations told Taproot there was room for improvement and things that slowed the result down. (Tim Querengesser)

Cameron Peters

- Scrutineer for: Michael Janz

- Where: Strathcona Baptist Church

- Arrived: 7:30pm

- Left: 12:10am

Cameron Peters said he observed what he called a "red flag" during the count at the station he scrutineered at, which was the arrival of different returning officers during the count. This perception, he explained, is based on his experience scrutineering for previous elections in Edmonton, all run under the Elections Alberta banner.

"I've never seen a situation where another supervisor was brought in to replace the returning officer, especially when the returning officer themselves is still in the building," he said. "What was (also) anomalous is that when I talked to the accounting supervisor, he disclosed that this was, more or less, his first job with Edmonton Elections, period, which to me seemed very strange, because I don't know what the hiring practices are for Edmonton Elections, but I've only ever seen it sort of being people who have worked as an officer or a clerk before."

Why does this matter? It meant there were extensive discussions to answer questions, consulting of manuals, and "people sitting and waiting for the next step," Peters said. He said several people who were supposed to show up to work the count didn't, which saw the leaders help out and staff that had been there during the actual vote work a long day.

Peters also said the system used was the same pass-around-the-table one Parkinson described, which he found frustrating. "It was agonizingly slow to watch because you had people just circling the same ballot potentially three times."

That delay ultimately saw some express frustration. They were paid a flat fee given counts at other elections are usually fast. He said some staff were deeply frustrated having to then work extended hours.

Max Amerongen

- Scrutineer for: Anne Stevenson (and assisted with Holly Nichol)

- Where: Robertson-Wesley United Church

- Arrived: 7:30pm

- Left: 11:30pm

Max Amerongen has scrutineered, to his count, 10 elections at different levels. He told Taproot that Edmonton Elections doing this sort of count for the first time versus tabulators in the past clearly affected its speed, agreeing with Parkinson on many of the basic challenges.

On the chaos some scrutineers described, however, Amerongen said this is normal. "I've scrutineered a lot of other races and there's always a bit of chaos," he said. "The count procedures break down a little bit, and then (there's) usually some, 'Oh, you missed a pile over there,' and 'Oh, there's a ballot stuck in the box,' or whatever. I think to someone who was scrutineering for the first time, it would have looked very chaotic, but it's always a little bit like that. That being said, I think it was their first time running one like this, so it was definitely less organized than a federal or provincial (election) that has the established procedures."

Amerongen noted a video from Edmonton Elections that showed four people handing ballots around in the method that Parkinson described. "I think, in a demo with four candidates that each have about the same number of votes, that procedure works great in a box with 20 ballots in it," he said. "But in a box with 700 ballots, where 400 of them are for one candidate, 100 are for (a few) other candidates, and then it's single digits for everyone else, and there's 10 or 12 candidates in the race, it broke down completely."

He said staff at the counting station he was at quickly modified this procedure to pre-sorting for major candidates into piles rather than passing them around. And he said he caught a 50-vote error in the public school trustee race between Holly Nichol and Amyjoy Clow, which he linked to the asymmetrical vote for Nichol.

As stacks of ballots travelled around the table, Amerongen said he saw one accidentally intermixed with a stack for the candidate who was in second. "I was looking over their shoulder and said … 'Hey, some of those are for Holly.' And so then they went through the pile again and found that there was a pile of 50 (ballots for) Holly intermixed … But they would have caught that on their own, too."

The count at Robertson-Wesley started at 9pm, Amerongen said, after there was an hour break following polls closing. It finished at 11:30pm. A fellow scrunineer he spoke with at a polling station where the voting line meant the station stayed open beyond 8pm said their count didn't start until 11pm, he said.

Amerongen also noted the loss of tabulators, adding the concerns about accuracy don't add up.

"It's a glorified calculator," he said of the tabulators. "The counters were using a calculator to keep track of their (stacks of) 50s. I don't have any worries about the calculator, either."

Correction: An earlier version of this story contained incorrect information from the source about how election workers will be compensated for extra counting time.