Applied Pharma facility could open local doors while bridging national gap

The head of Applied Pharmaceutical Innovation said a new manufacturing facility and start-up incubator that the company is building at the Edmonton Research Park should help spur a new wave of health innovation in the city.

Crews broke ground on the 83,000-square-foot Critical Medicines Production Centre in June, and it will nearly double API's footprint in Edmonton when complete in 2026. Andrew MacIsaac, CEO of API, said the plant will be able to produce more than 70 million doses of a vaccine, drug, or treatment yearly. In a crisis like another pandemic, MacIsaac said the facility could produce enough medicine or vaccines for all of Canada within 100 days.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada's lack of domestic vaccine manufacturing capabilities became clear. Canada's vaccination rate lagged behind that of other Western countries, partly because it had to rely on imported vaccines. In 2021, the federal government announced a Biomanufacturing and Life Sciences Strategy and has since dedicated $2.2 billion to enhancing the country's therapeutic production capability, especially for vaccines. API has received $80.5 million from the federal government and $17.6 million from the province to build the facility.

The production facility is a collaboration between API and the University of Alberta's Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute. It's partly funded by the $200-million Canadian Critical Drug Initiative.

MacIsaac said it's important for Canada to have domestic manufacturing capacity regardless of whether we're in a pandemic or not because it can increase supply-chain security for common drugs. Often, he said, massive facilities in other countries manufacture these drugs and produce enough to meet global demand. "As a result, they are able to produce a very cheap product that is cost-effective, but the challenge is if there's a disruption with them, it creates massive issues across the board from a supply chain standpoint, and a lot of these drugs are critical."

Take propofol, a common and low-cost sedative that's usually available but can cause major disruptions when it's not. Propofol is one of the first drugs the API facility will manufacture.

MacIsaac said the second reason a local facility is important is it can help commercialize innovations. While promising discoveries and developments are coming out of Edmonton's postsecondary institutions, he said the resulting economic activity is too often lost to other countries. "You know, there could be cures for cancer within a lab bench somewhere that, because of the challenges commercializing, (researchers in Edmonton) aren't able to take forward," MacIsaac said.

"It's an example of a sector where we have excellence from the academic side, but not the economic activity associated with it," he said. "In the life sciences sector, we're just about to hit the gas pedal and we'll start to see a lot more growth and development."

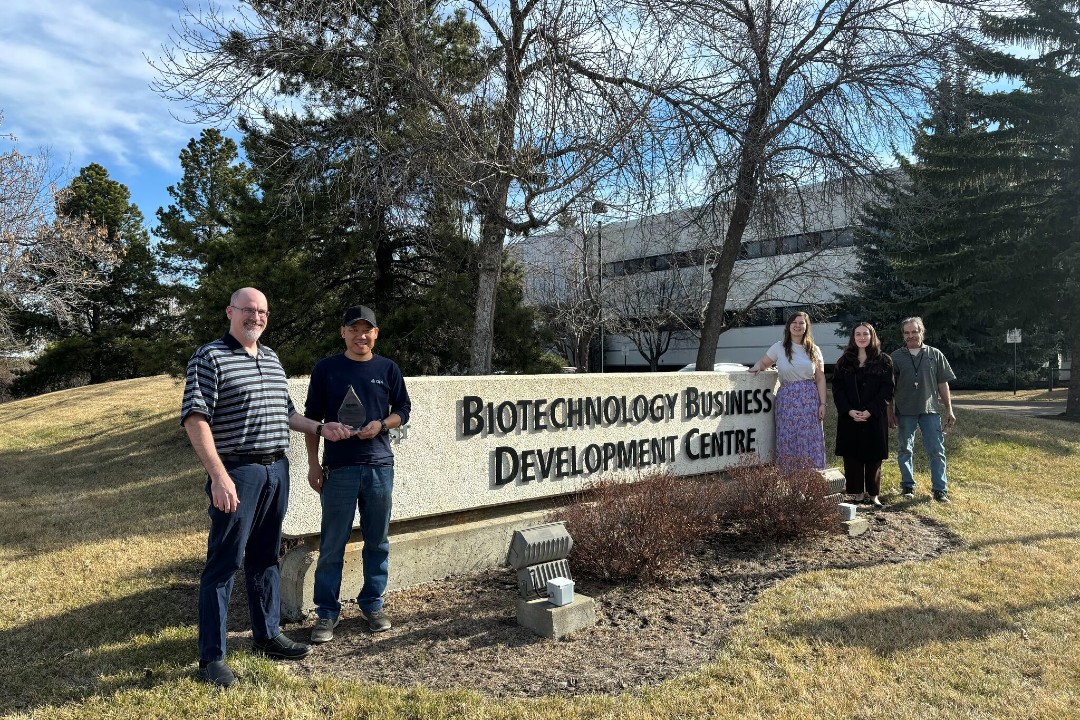

The new facility will also have space for health innovation startups. Across the street at API's Biotechnology Business Development Centre, MacIsaac said there are companies "bursting at the seams" that the facility will allow to scale up. "The goal is to basically build the runway for companies that are all the way from that first employee to that 30- or 40-employee company," he said. "Then at that point, they're getting to the scale where they're building their own facilities and moving forward."

API has also been established as one of the key advocates for the businesses that call the research park home. The company is co-chair of the Edmonton Research Park Advisory Group, a committee formed after a land sale created tensions between the City of Edmonton and entrepreneurs in the research park.