The federal government's recent push for cities to change rules that have limited dense housing near high-frequency transit has underlined new research, which shows Edmonton has not added population in many of these areas for decades.

On April 2, the Prime Minister's Office announced that to access a public transit fund Ottawa will introduce in the 2024 federal budget, municipalities must "take action that will directly unlock housing supply." Those actions include allowing high-density housing within 800 metres of high-frequency transit lines and post-secondary institutions.

The impetus is a desperate housing shortage across Canada. The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation projects the country needs to build 3.5 million additional homes by the end of the decade to restore affordability. Meanwhile, recent stats suggest Edmonton's housing starts were down 10% in 2023 as compared to 2022. The city was one of the fastest growing in Canada between 2016 and 2021. More than 100,000 people have moved to Edmonton since then and another 100,000 are expected in the next three years.

But despite this, new research suggests Edmonton has not added density on land that housing advocates say is most suited for density, and that new policies in the works may not fully fix that.

Jacob Dawang, a data scientist and a co-organizer of Grow Together Edmonton, has analyzed an 800-metre radius around 48 current and future LRT stations. Dawang also analyzed the city's draft district plans, which are meant to guide development as Edmonton grows to 1.25 million people. He found that population growth has been stagnant or even fallen within the proximity of nearly half the city's LRT stations, and that the forthcoming district plans don't specifically encourage increasing density near some of these stations.

Indeed, Dawang's analysis shows that between 2001 and 2021, the population grew by 10% or less near several stops, including the Meadowlark, Grovenor/142 Street, Glenora, Stony Plain Road/149 Street, Bonnie Doon, and Jasper Place LRT stops. His research also shows that, over the same period, the population has fallen near more than a dozen stops, including the Aldergrove/Belmead, Glenwood/Sherwood, and Millbourne/Woodvale stops. "There are a lot of stations in residential areas that have grown very little over the past 20 years," he said.

The findings are concerning, Dawang said, given Edmonton's increasing population. "We're growing at a super-fast rate … so we have to be ready. We have to be making these tough choices, and there will be growing pains, but these are really the tough choices and the tough discussions that we need to have if we're going to be growing by that much."

Dawang added that the city should maximize the return on the public dollars it has spent building high-frequency transit. "You have to remember that these are billion-dollar investments that we're putting into the LRT line. It's not someone's personal LRT line to take downtown. We really should be making the best use of these investments as possible."

A Valley Line Southeast LRT car runs southbound toward the Bonnie Doon Stop in this file photo. The federal government may make transit funding contingent on whether cities boost density allowances near high-frequency transit stops like those along Edmonton's newly-opened line. (Tim Querengesser)

The city's proposed district plans identify nodes and corridors across Edmonton that are ideal for denser development. According to the plan, the centre city node should have the densest housing, while major nodes and primary corridors should support low to mid-rise development. High-rise development should be located along larger roads within major nodes and primary corridors, the plan suggests.

Dawang's analysis found 13 current and future LRT stops overlap almost completely with a major node, the centre city node, or a primary corridor — which means the draft district plan explicitly encourages high-density housing.

However, about half of the stops have only a small amount of overlap, meaning the district plans don't explicitly encourage dense housing in an 800-metre radius around the stop.

"There are areas where those nodes and corridors just so happen to intersect with the transit station areas, but there are other station areas that are missed out by that policy, because the policy didn't really treat them as special areas," Dawang said.

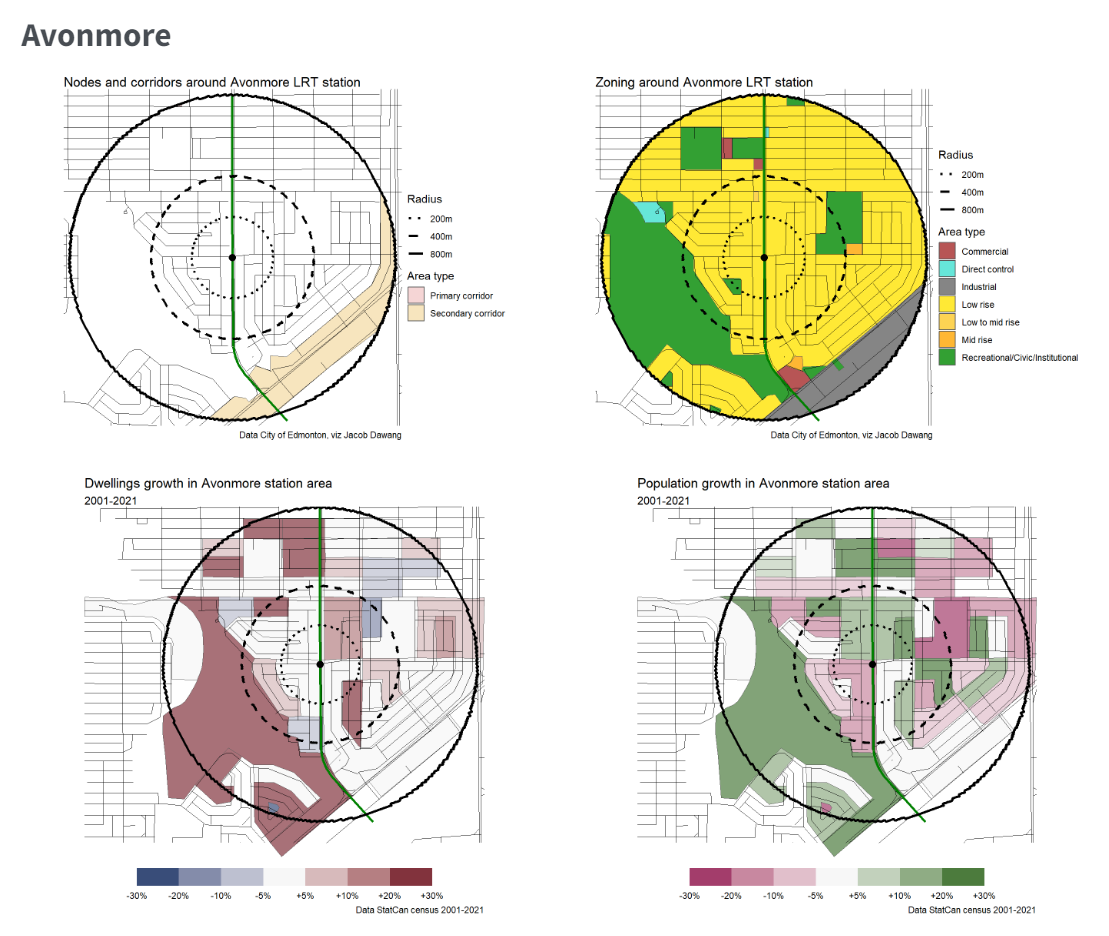

Take the Avonmore stop along the Valley Line Southeast LRT for example. Dawang found the draft district plan classifies about 10% of the land around the stop as a secondary corridor, which would allow housing to be up to four storeys tall, and housing up to eight storeys tall along larger roads that run through the portion of land. Most of the remaining land within 800 metres of the Avonmore stop, however, is only zoned to allow buildings of up to three storeys, with a maximum of eight housing units per lot.

Dawang's analysis found that between 2016 and 2021, while crews were laying LRT track in the neighbourhood, no new housing units were built within an 800-metre radius of the Avonmore stop, and population growth was flat.

Dawang said Avonmore is among the stops on the Valley Line with the least growth and the least amount of density encouraged, "but it's by no means the only one that has very little permissions for higher density under the draft district plans."

Still, some stations have seen growth. Clareview saw a 170% population increase between 2001 and 2021, while the population around the Alex Decoteau, NorQuest, and Bay Enterprise Square stops increased by more than 90%.

Avonmore's population was flat in the years before the Valley Line Southeast LRT opened. Most of the neighbourhood is zoned for buildings up to three storeys with a maximum of eight units per lot. (Jacob Dawang)

Meanwhile, a task force co-chaired by former mayor Don Iveson is also calling for increased density near transit.

The Task Force for Housing and Climate released Blueprint for More and Better Housing, which includes 140 calls to action for all levels of government. The authors argue the federal government should tie all infrastructure, transit, and housing funding to the adoption of pro-density housing reforms, including "ambitious as-of-right density permissions near transit."

The report calls for all provinces to consider adopting British Columbia's transit density rules for larger communities with high-frequency transit. The B.C. government requires some municipalities to allow building heights of at least 20 storeys for sites within 200 metres of a rapid transit station, 12 storeys within 400 metres, and eight storeys within 800 metres, among other regulations. The B.C. government said it estimates the new rules could lead to 100,000 new homes near transit over the next 10 years.

Edmonton already considers proximity to mass transit when looking at rezoning applications and development permits. The draft district plans do support high-density buildings near transit, but not as completely as Dawang, the task force, and the federal government are pushing for. The site must be in a primary corridor, along a major roadway, within 200 metres of a mass transit station, and allow for appropriate transition to surrounding development.

Dawang said the city should go further.

"When it comes to district planning, I think we need to either have another look, taking that B.C. policy as inspiration, or we need to be layering on another policy when it comes to transit-oriented development," he said.

The district planning policy is still in draft form. A report summarizing the city's most recent round of engagement on the plans is scheduled to be released this spring. There is a public hearing on district planning tentatively scheduled for May, the city said, and if the plans pass first and second reading, they will go to the Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board. If the board approves the plans, they are scheduled to come to council for a final vote in late summer to early fall of 2024.

The Prime Minister's Office also announced a $6 billion housing infrastructure fund through the upcoming 2024 federal budget. The money would first flow to provinces that commit to actions that increase housing supply, such as requiring municipalities to allow four units on every lot and more "missing middle" homes. If the budget passes, provinces would have until Jan. 1, 2025 to introduce these requirements, and if they don't, money would flow directly to municipalities.