As a public hearing approaches for a new policy that is meant to shape the development of the city as its population grows, some city councillors are worried the proposed plans could erode trust between Edmontonians and council.

If council votes for a first and second reading of the district policy after the public hearing scheduled to run from May 28 to 30, it will go to the Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board for review. The plans would then return to council for a final vote, which is scheduled for early fall. If approved, the plans will come into effect immediately.

Some councillors argue the draft district plans aren't aligned with other city-planning documents, potentially leading to confusion and anger as neighbourhoods evolve.

"Even the person who wants zero change (to their neighbourhood), at least they should know, based off the plans, here's generally what they should expect over the next 10 or 20 years," Coun. Andrew Knack told Taproot. "They will still be upset no matter what, but I think that there's a difference between being upset about how your city is changing versus at least understanding how you got to that point."

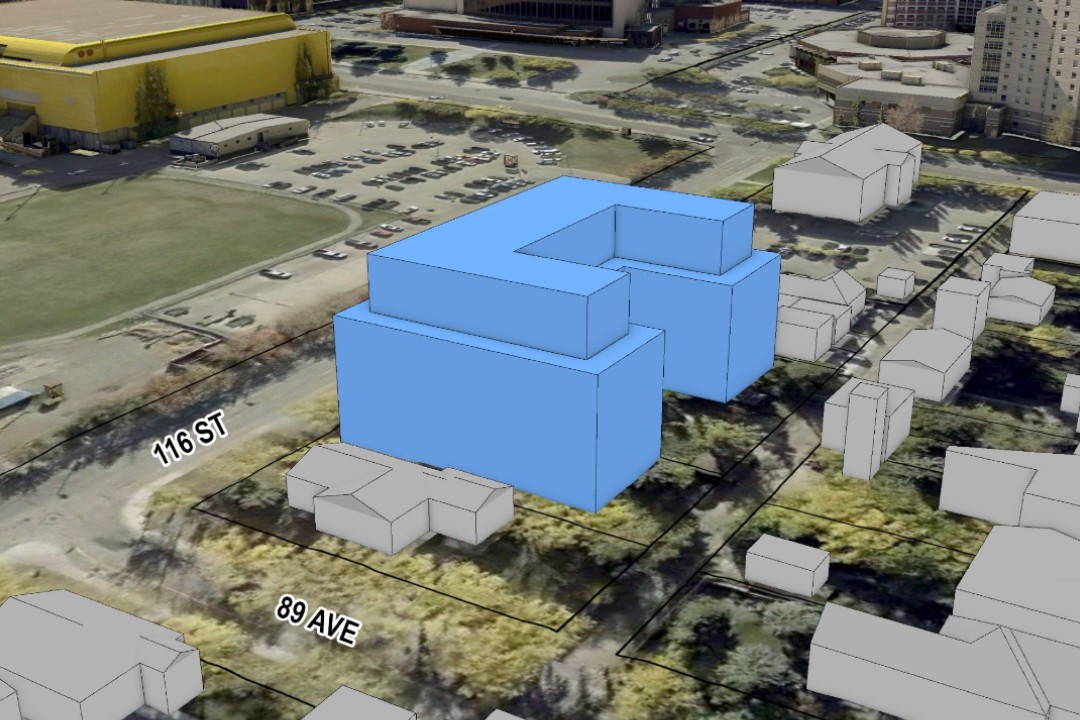

The potential misalignment came up in a public hearing for a rezoning in April, for a lot across 116 Street NW from the University of Alberta's main campus. The developer applied to rezone a parcel containing three single-family homes to allow for a multi-unit building up to six storeys tall. Even though the district policy is not in effect yet, some councillors brought it up during the debate. Given it is 100 metres from the nearest university building and 650 metres from the nearest LRT station, many councillors said it would have been a great choice for a larger building. However, according to the draft district plan, the site falls just outside a major node boundary, meaning the existing zoning allowing for only a three-storey building would be considered appropriate.

"I think there would be a very reasonable argument to say that the zoning in Windsor Park wouldn't have actually aligned with the draft district plan… even though from a practical land use perspective, all of the boxes are checked," Knack said in an interview. "It is absolutely the place where we should be doing something like that."

Coun. Erin Rutherford echoed this during the public hearing on April 22. She said there was no reason the area shouldn't welcome more density, as it is a high-growth area near the university and near LRT stations. "If our district plan is saying something different, even the interpretation of it by two councillors… that's still a percentage of Edmontonians that would likely interpret it the same way, and that's problematic," she said at the public hearing.

Rutherford said she was feeling déjà vu, as there have been several rezonings that didn't appear to align with the district planning documents coming before council in recent months. (Administration clarified that the project proposal would be aligned with district plans and recommended that council approve the rezoning. In the end, the rezoning was approved, with Knack, Sarah Hamilton, and Karen Principe opposed.)

Knack said the misalignment is not unique to the Windsor Park neighbourhood, and he believes conversations like this will return to council if the district plans are approved in their current form.

Edmonton city council approved a rezoning to allow for a building up to six storeys tall near the University of Alberta, with some questioning whether the building aligns with proposed city planning documents. (City of Edmonton)

Another area that he said does not align is the Valley Line West LRT route. He said in two neighbourhoods in his ward, the draft plans encourage increased density for only two blocks surrounding the route. At the Glenwood/Sherwood Stop at 156 Street and 95 Avenue NW, the draft district plans say about 90% of the land within 800 metres of the station should be buildings no taller than three storeys, with a maximum of eight housing units per lot. More density is encouraged on the lots on 156 Street, with the draft plan supporting buildings up to eight storeys tall.

"The City Plan would say no, there's got to be much more (density)," Knack said. "At a time where our population is growing as rapidly as it is, are we setting some unrealistic expectations?"

On the other end of the spectrum, recent changes to the draft policy allow for "expanded opportunities for taller, denser transit-oriented development." Knack said while he understands the intention behind this change, the criteria still feel open-ended. "It's created uncertainty from the community side, but I've even talked with the folks in the development community who find that has created uncertainty on their end, too."

He mentioned an email he received from the Coalition for Better Infill, a group that says it is "deeply concerned about the city's deregulation of the infill development industry." The group encouraged people to talk to their councillors about the changes introduced in the new zoning bylaw in 2023, and is now encouraging the same for the district policy. Knack said the group was alarmed that 20-storey towers could be built near transit. "I think that is truly a bit of fearmongering, but at the same time, the way (the district plans) are worded, you can see how they can try to make that case," Knack said.

So what are the district plans, how do they work, and what will they do?

What are the district policy and plans?

The plans have been in the works since the city council of 2020 approved the City Plan. The district policy is meant to provide more nuanced direction than the City Plan. While the City Plan says, in general, housing density should be concentrated along major roads, near large employment centres, and close to mass transit, the district plans take the neighbourhood context into account.

Specifically, the district plans are meant to get the city closer to two goals laid out in the city plan. The first goal is to add 50% of new housing units through infill. The second is to have 50% of trips made by transit and active modes, while ensuring Edmontonians can easily access their daily needs within a 15-minute walk, roll, or transit trip.

How will the district policy attempt to do this?

In the draft district policy, there are 15 districts. The districts have nodes and corridors that are meant to see varying levels of housing density and a mix of uses built as the city grows.

Nodes are urban centres that serve multiple neighbourhoods, such as the University of Alberta or Capilano Mall. There are major nodes, district nodes, and local nodes, with more density allowed in the major nodes and less in the local nodes. There's also the city centre node, encompassing downtown, Wîhkwêntôwin, Chinatown, and other central neighbourhoods, where the density permissions are the least restrictive.

Corridors are prominent thoroughfares, and include much of Whyte Avenue, Stony Plain Road, and 137 Avenue, for example. There are primary corridors and secondary corridors. While the corridors are centred around these major routes, they extend a few blocks into the surrounding neighbourhood.

Throughout primary corridors, the plans support buildings up to eight storeys tall. If the lot is along an arterial roadway, or within 200 metres of a mass transit station, the building can be up to 20 storeys tall. The building can be even taller if it meets both of those criteria and can transition appropriately to surrounding developments, according to the draft plan. Throughout secondary corridors, the plan supports buildings up to four storeys tall, and up to eight storeys tall if the lot is along an arterial or collector roadway.

What will the plans actually do, if approved?

The plans would not automatically rezone any properties if approved, unlike the zoning bylaw renewal, which rezoned the entire city. The policy provides planning direction. When a developer applies to rezone a property, city administration will be able to recommend that council approves or rejects it, based on whether it aligns with the district plans for the neighbourhood.

However, if the district plans are approved, city administration will undergo a project to pre-emptively rezone priority growth areas. That rezoning project is scheduled to go to a public hearing in the first months of 2025.

Also, administration says the plans aren't the be-all and end-all of development in Edmonton. Just because a property isn't within a node or corridor, it doesn't mean it will never be developed into a multi-unit building.

How do the district plans affect transit-oriented development?

Following changes introduced in April, the draft plans now consider proximity to mass transit in node policies. Previously, this factor was exclusive to corridor policies. The new plans for major nodes now support buildings up to 20 storeys tall within 400 metres of a mass transit station and buildings taller than 20 storeys within 200 metres of a mass transit station. Within district nodes, the plans support buildings up to eight storeys tall within 400 metres of a mass transit station and buildings up to 20 storeys tall within 200 metres of a mass transit station.

Jacob Dawang, a data scientist and organizer with Grow Together Edmonton, analyzed the previous and current draft district plans and how they may shape the land around current and planned LRT stops and stations. Dawang said earlier versions of the draft plans were a missed opportunity as they didn't use transit centres themselves as a trigger that would allow for higher density. The area around some transit stations does not overlap much with node and corridors, meaning the district plans don't necessarily encourage building high-density housing around those stations.

The new factor introduced in April doesn't change much around transit stations, according to Dawang's updated analysis. He said the change is a "step forward" and there are many additional sites that would be considered for extra density within 400 metres of transit. However, after he saw the hesitation from some councillors during the public hearing for the Windsor Park rezoning, Dawang was less optimistic about the transit proximity factor. "That kind of put me on the other side of that. This is not enough — we need a policy that says explicitly that we will outright support mid-rise housing within 800 metres or (within) walking distance of transit," he said.

The 800-metre radius has emerged as something of a gold standard for transit-oriented development across Canada. The Prime Minister's Office said cities need to allow high-density housing within 800 metres of high-frequency transit in order to access an upcoming federal public transit fund. B.C.'s provincial government requires some municipalities to allow building heights of at least eight storeys within 800 metres of high-frequency transit, and up to 20 storeys within 200 metres. Former mayor Don Iveson co-chaired a task force calling for all municipalities to adopt "ambitious as-of-right density permissions adjacent to transit lines."

What's next?

The city encourages those interested in sharing their views on the district policy and plans to sign up to speak at the public hearing on May 28.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify council and administration's position on the Windsor Park rezoning.