Edmonton's river valley is a cherished nature getaway for many Edmontonians. Canada's largest contiguous area of urban parkland didn't come about by accident, however.

As Episode 65 of Let's Find Out demonstrates, it was the product of generations of like-minded Edmontonians banding together to preserve a piece of beauty in a time of rapid industrial and residential development. In the case of Borden Park and Coronation Park, it required putting down some serious cash without knowing whether it would pay off.

"I think the story of these two parks is worth telling," said Dylan Reade, a documentary filmmaker and researcher called in by podcast host Chris Chang-Yen Phillips to help answer a question from Zulima Acuña about how and why some of Edmonton's river lots became parks.

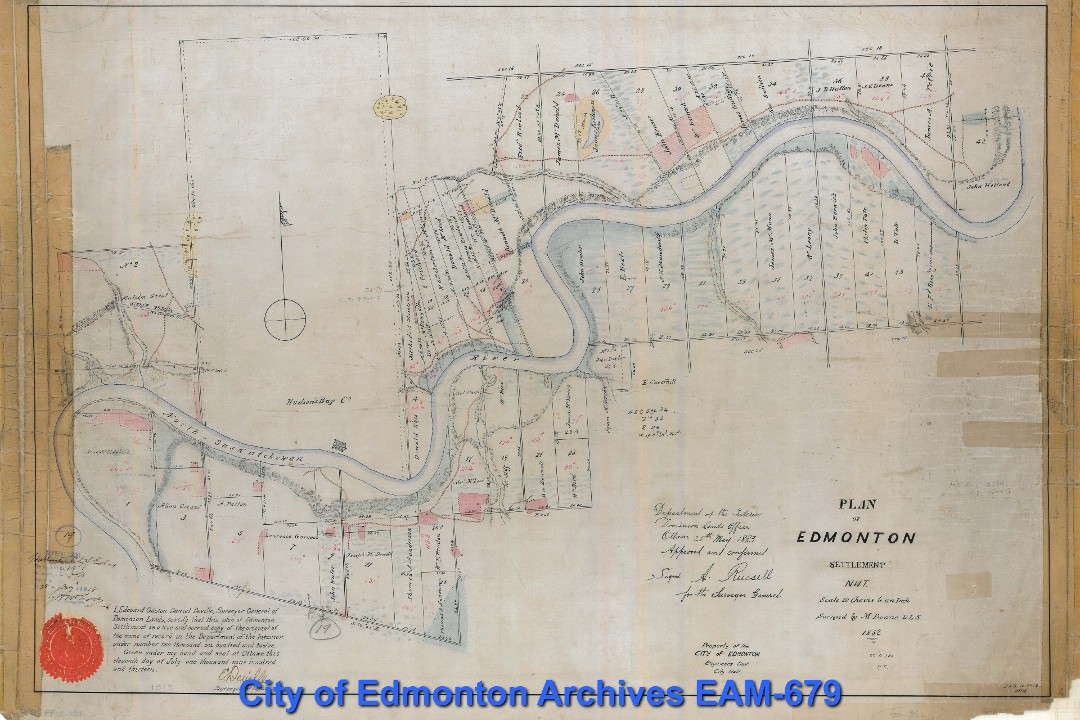

When the land was surveyed in 1882, the map formalized 44 long, skinny lots along the banks of the North Saskatchewan River, conforming to the practices of the largely Métis population at that time, wrote Connor Thompson, who was also enlisted to answer Acuña's question.

By 1900, almost all the land that makes up what is now Edmonton's downtown core had been purchased by investors, families, and businesses. Soon, what had been a small settlement surrounded by parkland was now a growing urban area in which people were rapidly buying up whatever natural space remained. By 1907, citizens and landscape architects such as Frederick Todd were advocating for the preservation of what was left in the river valley as part of the City Beautiful Movement.

At one point, two major properties came up for sale: the Bouchard estate and the Kirkness estate. But the mayor and several council members were in Winnipeg on holiday, Reade said, and given the rapid pace of real estate transactions at that time, they wouldn't be back soon enough to authorize the City to put down a bid. So the aldermen who were still in town ponied up the cash themselves and purchased the land in the hopes that city council would agree with their decision upon their return.

Their gamble paid off. The Kirkness estate would become the East End Park, which eventually became known as Borden Park. And the Bouchard estate begat the West End Park, later Coronation Park.

"It's because of those aldermen that those parks exist now," Reade said.

This land transfer is just one moment in an expansive tale explored in the June episode of the podcast, which answers questions about Edmonton's history.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that while Edmonton's River Valley is indeed very big, it is not the largest urban park in Canada.